Society alumni shaping the future for Black scientists

Black scientists and engineers make up approximately 9% of the STEM workforce, according to a 2021 report from the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. That number has increased since 2011, when Black workers accounted for only 6%.

Throughout history, many pioneers have made remarkable contributions to STEM fields. Among them is chemist Alice Ball, who developed an injectable treatment for leprosy; she wasn’t recognized for her work till 6 years after her death. Astronaut and aerospace engineer Guion Bluford became the first African American in space during the Challenger’s eighth STS mission. Mathematician Gladys West played a crucial role in processing data that contributed to the development of the Global Positioning System (GPS).

Nancy Agnes Durant, Science Talent Search alumna, has also made history as the first Black finalist in the most prestigious science and math competition in the country. She is and has been a trailblazer for future Black scientists.

Augusta Uwamanzu-Nna (STS 2016) and Nyasha Nyoni (STS 2022) represent younger Black Society alumni. In her STS project, Augusta studied the impact of adding nanoclay, (a grain clay mineral made of nanoparticles) to cement seals to protect undersea oil wells and avoid leaks. After completing her bachelor’s in bioengineering and biomedical engineering from Harvard, Augusta is pursuing the path of physician-scientist at the University of California, San Francisco. In this role, she hopes to develop equitable and accessible diagnostics for underserved communities. In her STS project, Nyasha explored how influencers recommending unhealthy foods could have a detrimental impact on health decisions made by young people. Currently, Nyasha has taken her talents to the University of Miami, where she is studying Motion Pictures on the business track.

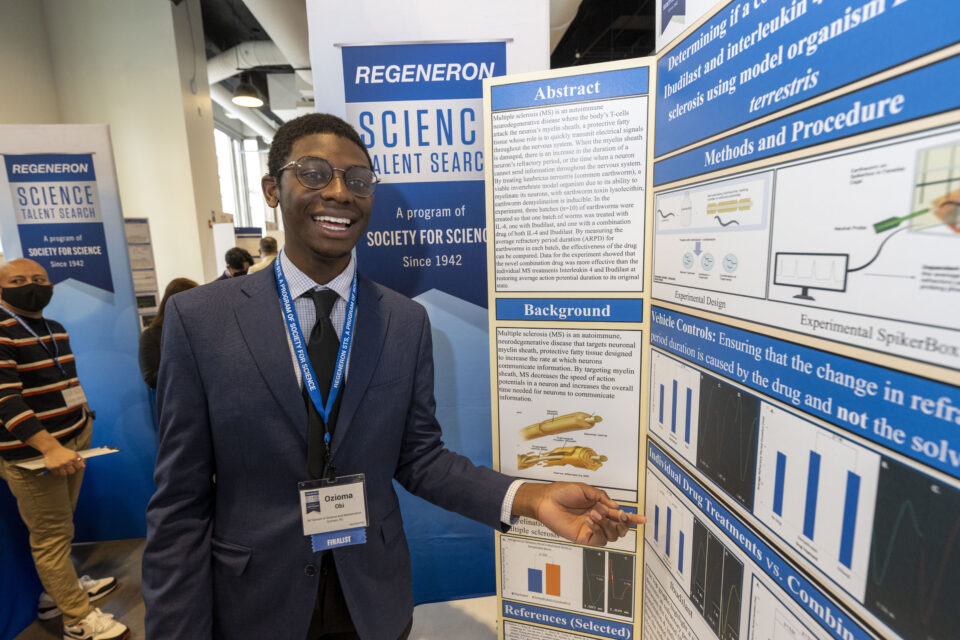

We also recently had a chance to catch up with another recent alum, Oziomachukwu (Ozioma) Chidubem Obi (STS 2023). In his project, Ozioma investigated how a combination of drugs could potentially address neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis (MS). Ozioma gained inspiration from his late grandfather, who was the first nuclear physicist in the entirety of Nigeria. While his grandfather lived with his family in the U.S., he says his grandfather would engage any house guest in scientific conversation. After his grandfather was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, Ozioma decided that he wanted to study neurodegeneration for his STS project. Ozioma’s brother, Nnamdi Obi, an STS top scholar, also studied a similar topic.

“I actually had an innate goal to get further into biological research than my brother,” Ozioma explains. “It wasn’t long after that I truly fell in love with neuroscience and the one-sided brotherly competition fell to the wayside.”

Besides his brother, some of the other Black scientists and innovators that he looks up to are his friends.

“I was fortunate enough to be surrounded by a high school community of Black researchers and minds that all shared a want to impact our communities,” Ozioma says. “I was also inspired and stimulated by the diverse interests of my friends, who I’d learn something new from every day.”

Currently, Ozioma attends Harvard, where he studies neuroscience and philosophy while being heavily involved in campus life. From being a violinist in the Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra to being a researcher in the Kuchroo Lab, a dancer in Harvard’s Omo Naija X Wahala Boys African Dance Troupe and serving as the editor for the Harvard Review of Philosophy, Ozioma keeps himself busy.

Although he sometimes feels alone as one of the few people who look like him in a room, he remains resilient and determined to make his dreams a reality.

“I remind myself that I’m just a Black kid who loves what I love, and to me, there’s nothing more to it. I would never want to be anything other than Black,” Ozioma says. “My situation is not unique; there are so many Black voices in STEM fields that have yet to be heard, and so many issues (STEM and non-STEM related) that afflict our various Black communities daily, that haven’t even been brought to the table. Representation will never not matter.”

Ozioma’s grandfather had a saying in Nigeria’s Igbo: Mmadụ niine nwe ofu isi. Ọ dirọ onye nwere isi abụọ. Translated, it means: “Everybody has one head. Nobody has two heads.”

“The meaning of this saying was that everyone can shine in the things they do. Being Black in STEM is no different; strive for the best in the things you are passionate about and take pride in what you love,” Ozioma says. “STEM isn’t easy, and there have been many times when I wanted to leave STEM out of discouragement, but each time I look back, I’m so thankful I persevered.”