Alumnus and subscriber helps found Southeast Alaska science fair

Bill Leighty won a fourth award at the International Science and Engineering Fair in 1961 and is a long-time Science News reader and subscriber. He went on to a career including electrical engineering, restaurant ownership, and much more. He helped found the Southeast Alaska Regional Science Fair and currently owns Alaska Applied Sciences, Inc. which consults on science, renewable energy and conservation.

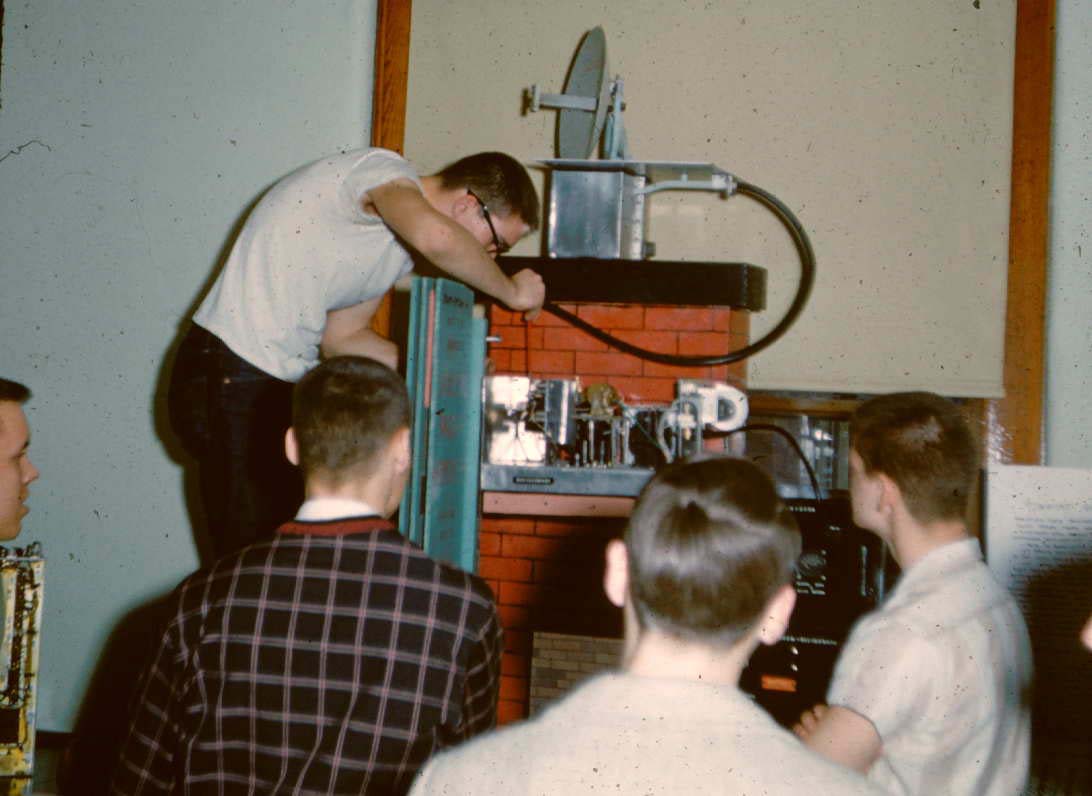

I competed at ISEF in 1961, my senior year at West High School in Waterloo, Iowa. The emphasis was not yet focused on disciplined research, as it is today. And the rules were many fewer and much more open, leading to more fun and entertaining “hands-on” projects and exhibits. We could display live plants and animals, water and other dangerous substances, and demonstrate our equipment.

I shared a room with Bob Olds, the other delegate from the northeast Iowa science fair. At the time, the fair sent two delegates every year, one in biology and one in physical science. I had just started trying to smoke, and I remember Bob didn’t appreciate my doing so in the hotel room. I also remember meeting a lovely female delegate with whom I had a long conversation on a park bench.

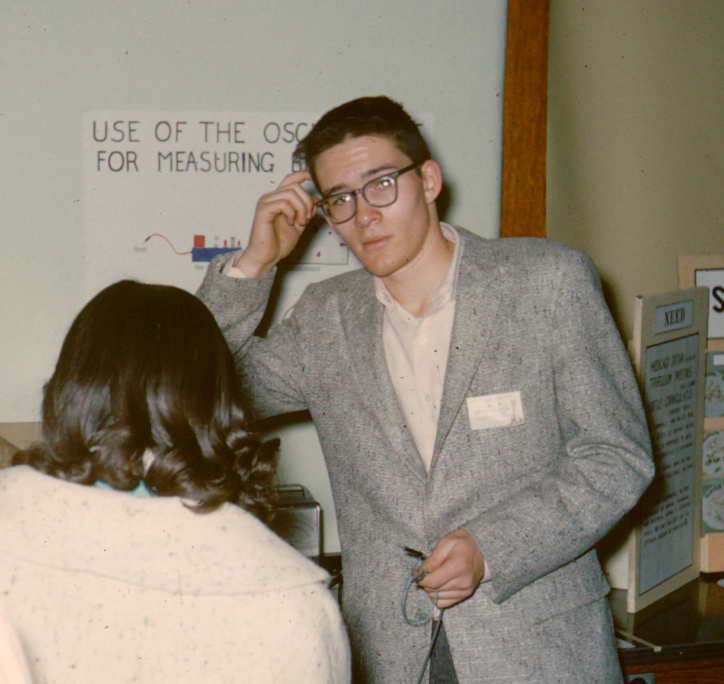

I really wanted to get out of Iowa, so I made a hand-printed sign advertising myself for a summer job in California. The director of the Marine Physical Lab at UCSD-Scripps Institute, Dr. Victor C. Anderson, happened to come by and see the sign; his daughter was also a competitor that year. He told me to write a letter to the Lab, and I ended up getting a fantastic summer job in San Diego because of that, where I got my hands on a Tektronix 545 oscilloscope, the “Cadillac” of oscilloscopes at the time.

Competing at ISEF was a great experience. The prestige, the honor, being interviewed and selected by the judges, and winning the admiration of peers and science teachers was all important in encouraging me to continue figuring out how things worked and how I could make them work.

How did you get involved in science fair?

It really began when I moved with my mother as a baby to live on her parents’ farm in east central Illinois; this was in October 1943 when my father was away at war in the Pacific. As a toddler, I tagged along with my grandfather, and farmers are always working on and fixing things.

I also had really good science teachers beginning in sixth grade. And I wanted to do hands-on things and that’s what science fair projects were. I became fascinated with electronics very early on. I was given a car radio out of a 1940 Buick and converted it to run on household electricity in the fifth grade. I couldn’t enter the science fair until ninth grade, so I planned my first science fair project for two years.

In eighth grade, I saw David Ecklein’s (another ISEF finalist) science fair project measuring distance with sound. He was a couple of years older than I and built it with war surplus materials. After that, I decided I could build an oscilloscope; I wanted to use it for measuring brain waves. Once I got started, it was sort of addictive. At that time a lot of WWII surplus material was available for not very much money, and every time I went to Chicago to visit my uncle I got to bring back as much as I could haul from surplus stores there.

Sputnik, in October 1957, was also an inspiration for lots of people getting into science fair and engineering at that point. The culture at that time was for high school science teachers and parents to be on board and encouraging. We were helped and honored by our peer group, school, and community if we had science and engineering potential. It was almost patriotic.

My father was a salesman, sales manager and small business founder and owner. He and a partner had won the 1934 Cedar Falls science fair with a project on an electroplating system. I learned from him about promotion and self-promotion for my project, how to sell it to the judges, have my pitch ready, and how to design the project to get attention.

Can you provide a short description of your research project and how you initially became interested in this topic/science in general?

I had been competing in science fairs since the ninth grade, and since then, my schedule was to give myself a few weeks off after the science fair was held at what is now University of Northern Iowa and then start the next year’s project.

My senior year project was called SETIME (Semiautomatic Electronic Time Interval Measuring Equipment). It had never been built before, and I read about it in a booklet published at that time called Inventions Wanted by the Armed Forces. They wanted a machine that would measure time intervals with an accuracy of 1 microsecond.

It didn’t end up working, but that was my goal. Judging at the time was based as much on effort and whizbang as collection and analysis of data, and there were much broader exhibition guidelines than today. I built it using WWII surplus parts, and used a computer magnetic memory drum donated by Burroughs, Minneapolis.

How did doing original research and participating in events like ISEF affect your education and career trajectory?

Having succeeded at the high school science fair level in electronics, I felt prepared and dedicated to studying electrical engineering in college. It was the obvious thing for me to do. My father took me to visit with a friend of his who was on the faculty at the University of Iowa to talk about which were the best engineering schools in the country, and he said MIT and Stanford. I chose to go to Stanford, because I wanted to get farther away from Iowa and thought it was the Golden West with beautiful women.

After college, I took my first job doing systems engineering at Collins Radio Company in Iowa. I worked at Collins for two years in Iowa, and then for a year and a half in Southeast Asia. I didn’t want to be in the military, but I had buddies in the war in Vietnam, and thought I should go help. After that, I decided to go to graduate school for business. I had always been interested in business, and an MBA plus an electrical engineering degree seemed like a good thing to do.

After graduation, I didn’t really like the job offers that were appearing. But there was one from the State of Alaska for a budget analyst. At that time, it was fashionable to believe that modern management techniques could be applied to the public sector as well as the private. Four of us got hired and came to Juneau. Then, I got fired after 6 months- everyone should be fired at least once. If not, you’re not trying hard enough.

So, in December 1971 I had just been fired, it was cold and I was living on a houseboat. I got a job with the Juneau Model Cities program, and after some time, my boss told me I didn’t belong in government work and suggested that I buy this outdoor restaurant he owned with a partner. I ended up buying it for $750 and running it for 18 years, and it helped me meet my wife. We sold the restaurant in 1990, which allowed me to go back into engineering, and then founded a company focusing on science education and renewable energy. We have built a computer-guided telescope used in Hawaii and wind generators and a wind plant in southern California. I have co-authored many technical research papers on alternatives to electricity for transmission, storage, and integration of large, renewable energy resources — as hydrogen and ammonia fuel systems, which may be necessary for us to “run the world on renewables,” as we must.

How did you get involved with science fair in Alaska?

I had maintained my interest in science and engineering the whole time, and I did a lot of volunteering in local schools. When our younger son was in ninth grade, six of us got together and decided to start a science fair in Juneau. That was 21 years ago. We had both business and school district support.

In our first year, we only had six projects (one of whom was our son, who got talked into it) presenting at the local mall. But the second year, we had 30-40 projects and now we have more than 100 projects and 150 students participating each year. NOAA’s Ted Stevens Marine Research Institute even has two research staff members who have it written into their job description that 20% of their time will be spent on organizing the local science fair. There are a lot of scientists in the community, mostly marine biologists, and they do most of the mentoring and judging.

Science fair value, in a few words: entrepreneurial, community building, responsibility, discovery, and personal growth.

Do you have any advice for young students interested in science?

Science is great fun and human beings are naturally curious and like science. Be human and let yourself discover. Do things. Make mistakes. If you are at all interested in physical sciences, get junk office equipment and take it apart. You can usually get old copiers and equipment for next to nothing, just for the fun of taking it apart and recycling. Figure out how things work and why they did it that way. It’s a really inexpensive way to get interested in science, especially electrical engineering.

We desperately need adults who understand how the world works. How are we supposed to make decisions about managing the planet when can’t even read the instruction book? Without science and engineering literacy, we are lost when deciding what to do about the energy problem, which I think is the most interesting and urgent problem we are currently dealing with.

In short, science is fun and rewarding. We need you, and there will probably be a job waiting for you. Think like an entrepreneur. Think about what the creative and business opportunities are in an area of science that interests you. Subscribe to some science magazines, like Science News, and read.

You also are a long-time subscriber to the Society’s Science News magazine. Can you tell us what you most appreciate about the magazine? Why have you continued to subscribe?

It provides a good service to many people with a broad spectrum of interest in science, and I thought continuing to subscribe was the best way to support that. Both my wife and I enjoy reading it; she’s a former 1st grade elementary school teacher. I subscribe to several engineering and energy magazines as well. When I’m done with them, I give them to my neighbor for his middle school-aged kids, and I hope they read them. It’s important to subscribe, pass it on, and read about science.