Spotlight Series: National Leadership Council member, Nevin Summers

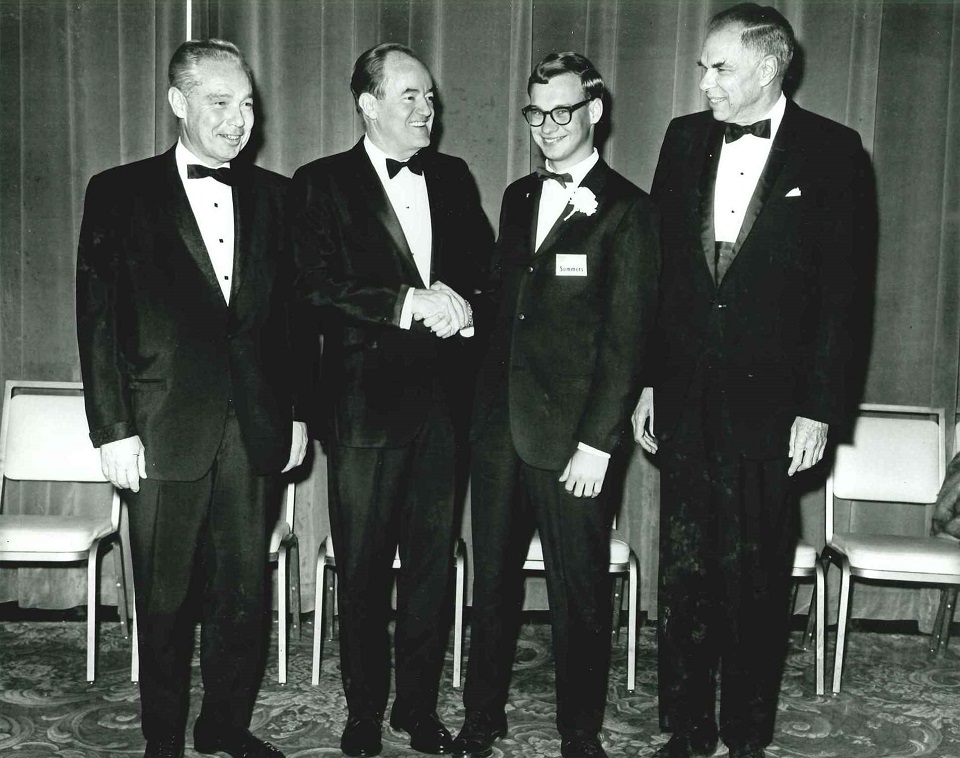

Name: Nevin Summers (STS 1967; ISEF 1965-1967)

Job Title: Executive Director of the MIT Synthetic Biology Center

About Nevin: Nevin currently serves as Executive Director of the MIT Synthetic Biology Center, where he is responsible for building collaborations between academia and industry, including startups and corporate-sponsored research. He works closely with multi-disciplinary Synthetic Biologists who combine insights in computer science, DNA engineering, gene editing and directed evolution to iteratively design, build, test, and improve beneficial bio-molecules, viruses, cells, organisms, and ecologies that can offer transformative, renewable, sustainable, and socially equitable solutions to critical unmet global societal challenges

Education: B.S. in Molecular Biology from Johns Hopkins University, M.Arch. from Harvard University, and S.M. in Management of Technology from MIT.

What does leadership mean to you?

A leader faces an especially daunting challenge. To motivate others to take a risk doing anything with you, you must first convince them of your integrity, competency, reliability, mastery of the facts and analytics pertinent to your proposition and, most of all, your demonstrated passion and commitment to achieve a major objective that resonates with their values and aspirations. For me, learning to be a leader was in the doing. My training as an architect and project manager, and the economics of a construction boom in Boston, offered me the chance to jump into the deep end of the pool and learn how to swim. I had to train myself on how to finish one project while marketing the next.

As the world faces a pandemic, a climate catastrophe and numerous other scientific challenges, what are some steps you think the Society can take to address science literacy and support for science?

The validity of modern science itself is being questioned, even while the benefits of modern technology are taken for granted without any thought about the many scientific principles underlying their existence and operation. Everybody expects their iPhone to just work. Ignored is the fact that centuries of science have preceded it.

The Society for Science, through its distinguished 100-year history, mission and accomplishments in science journalism, competitions and other educational outreach programs, stands in stark contrast to these untenable positions. What more could the Society do to defend science?

I wish we had more politicians in government that were STEM-trained. This would dramatically raise the level of discourse. For instance, ISEF could have a new category: “Science and Technology Policy.” There are many important policy issues (and future career opportunities) here for students to research — they are frequently covered in the Society’s Science News magazine.

What is the most fulfilling aspect of your job?

Archimedes famously said, “Give me a place to stand, and a lever long enough, and I will move the world.” The place where I’ve chosen to stand and dare to make the world better is in a Synthetic Biology lab at MIT, and the lever I’ve chosen is the ability to read and write genetic code in DNA and then put that DNA into the genome of a living cell to program new and useful biological function. As an Architect registered in Massachusetts, I focus on biological design. Instead of choosing concrete, steel and glass to build non-living structures like skyscrapers, I’ve chosen DNA, RNA and protein to build living structures like genetically engineered cells for transplantation therapy or for the production of antibodies and other therapeutic proteins. The basic engineering principles of abstraction, standardization, modularity and systems analysis apply to both inanimate and animate design realms.

The most fulfilling aspects of my job, now that MIT buildings are open again, are in-person lab meetings and simply sitting at my desk in a large cubicle farm and talking with nearby grad students and postdocs about the experiments they’re doing in the lab down the hall. It is very gratifying to witness their growth as scientists and engineers, and to help them whenever I can.

Is there a book that has made an impact on your life? What is the name of the book and what impact did it make?

Many books have made an impact on my life. I will mention two: one that has kept me optimistic during the pandemic and another that convinced me fifty years ago to completely change my career from molecular biology to architecture.

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism and Progress by Steven Pinker (2018):

I started reading this book shortly before the pandemic began. Steven Pinker makes the case that the existential state of humankind has significantly improved over the last 300 years. Reading the “long view” presented in this book was, and is, very comforting to me, especially in the early days of COVID-19 when the death count was exponentially rising, and we had no available diagnostics, prophylactic vaccines or therapeutics. All we had were face masks, hand washing and social distancing — the same approaches used during the 1918 influenza pandemic when over 50 million died worldwide.

Are we better off now?

I don’t think there’s any doubt that we are. We have PCR and immunodiagnostics, several forms of vaccines including those made of mRNA as well as antibody and small molecule therapeutics. Governments are more responsive to the needs of their citizens. Nothing will ever be perfect, but the quality of life is steadily improving. We will discover and implement solutions to the many challenges ahead of us. STEM-literate citizens will lead the way.

The second book I mentioned is Scope of Total Architecture by Walter Gropius (1943). In the book, the author presents his philosophy of architecture in the service of society. The architect is a coordinator, a person of vision and professional competence “whose business it is to unify the many social, technical, economic and artistic problems which arise in connection with building.”

At age 23, I stood at a crossroads in my career. I had my B.S. in molecular biology, worked in a lab at Stanford Medical School, and had been accepted into the Ph.D. Program at Stanford Biology. The Vietnam War was raging. I had been doing science since I was 14 and felt burnt out.

This book sparked my interest in training to become an architect. The more I explored the career the more I realized that I could leverage my STEM skills and develop that personal humanistic foundation I was looking for. I moved to Boston and enrolled in night school at the Boston Architectural Center, but ultimately found difficulty getting work during the 1974 recession. As luck would have it, I met Walter Gropius’ widow, Ise, who hired me as a part-time gardener and, eventually, as an assistant organizing all of Walter’s architectural photographs, letters, publications and press clippings. I did this for nine years until her death in 1983. She was an amazing person and a mentor to me.

Did you have a favorite mentor as a young person? What difference did that person make in your life and your approach to problem-solving?

There are way too many to name so I will just mention the first one that got me hooked on doing research. My first science class was in 1962 in the eighth grade and was taught by Mrs. Nelle Norman. One day, she introduced us to the scientific method. This got me excited! Growing up in Florida with its diverse flora and fauna, I was always curious about what crawling creatures I could find by turning over a rotting log in the woods near my home. Apart from simply looking at living specimens in the wild, I knew nothing about them, except what I could find in an encyclopedia. Suddenly, I was empowered to actively leverage my curiosity by creating hypotheses, designing experiments/controls and generating data by myself. My passive observational perspective totally changed forever when Mrs. Norman gave her lectures on the scientific method as the essential tool for humankind to better understand the universe, and, as I would later discover, to inform the many personal decisions one makes in life.