Alumni, ISEF, Science Talent Search

Network of peers formed at science fair ‘invaluable’

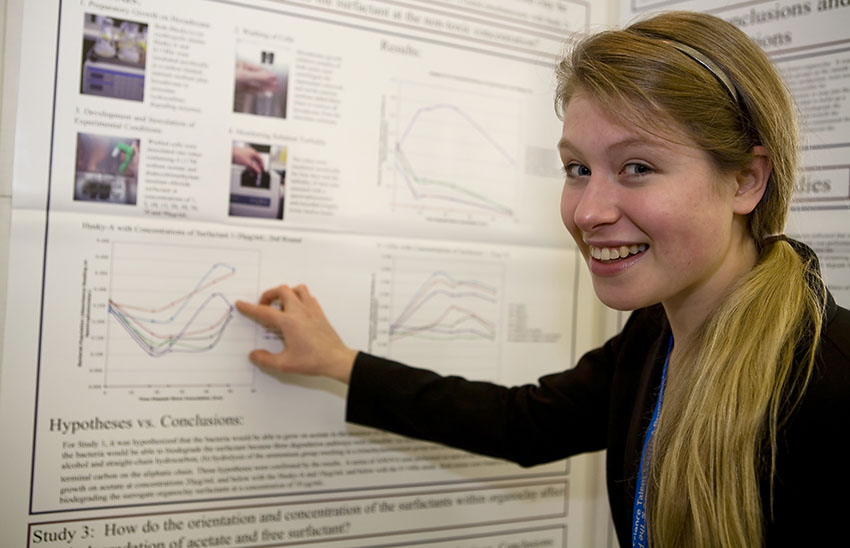

Not everyone gets to be called an academic rockstar by none other than President Obama. For Laurie Rumker, it’s a typical compliment.

Every year, several Society for Science & the Public alumni are chosen to participate in the White House Science Fair. Laurie participated in Society programs including the 2007 DCYSC (Discovery Channel Young Scientist Challenge), Intel ISEF 2009-2011, and was a 2011 Intel STS finalist, and attended the first White House Science Fair in 2010.

She developed a network of peers through the White House Science Fair and Society competitions. These communities “had a profound, positive impact on my self-understanding and career aspirations,” she said.

Read the interview below to learn more about Laurie’s endeavors as an experimental scientist.

TELL US ABOUT YOUR VISIT TO THE WHITE HOUSE: I was fortunate to be a member of the Society delegation to the first-ever White House Science Fair in 2010. The most memorable part of my visit was meeting President Obama and sitting on the stage behind him as he delivered a speech on youth involvement in STEM pursuits.

Being part of a group of young people referred to as academic rockstars by one of the most powerful individuals in the world was truly inspiring. Recalling that moment and message continues to encourage me today.

The White House Science Fair gave me, and continues to give students, that invaluable validation and inspiration. I am extremely grateful!

Help inspire other young scientists like Laurie into science. Join the Society today!

WHAT ARE YOUR CURRENT STEM GOALS: I studied human biology at Stanford University and received a coterminal master’s degree in biomedical informatics at the Stanford School of Medicine. I’ll enter medical school next fall.

The project that brought me to the White House Science Fair explored the impact of microorganisms on an innovative tool for protecting rivers from toxic chemicals that were being used at a Superfund site in my hometown of Portland, Oregon.

Being referred to as an academic rockstar was truly inspiring.

My interest in microbiology continued throughout my undergraduate studies, where my application focus shifted to the human body. I investigated the stability and resilience of the microorganisms that dwell in the human gut.

This work culminated in my honors thesis and was recognized by the Stanford faculty with a Firestone Medal for Undergraduate Research.

ON COMMUNITIES SHE FORMED THROUGH STEM COMPETITIONS: My fellow student researchers have remained an important part of my life, from being editorial collaborators at the Stanford Undergraduate Research Journal to being housemates and close friends.

Students from underrepresented groups within science and engineering, and those who face discrimination, are more likely to internalize failures.

Underrepresented groups specifically benefit from competitions like the White House Science Fair and Society programs. The mentorship and encouragement these groups experience in these programs is invaluable.

ON THE IMPORTANCE OF MENTORSHIP: I was fortunate to receive support from mentors who recognized and fostered my early passion for scientific exploration.

But many students lack access to educational curricula that emphasize curiosity-driven learning — the true heart of science at all academic levels. Many are discouraged from careers in science on the basis of characteristics like gender and ethnicity.

Throughout my own career as a young scientist, I’ve felt a responsibility to introduce other students to research opportunities and provide them with support.

Being an experimental scientist requires confidence because it inherently involves a substantial amount of failure as an essential component of learning and discovery.

Students from underrepresented groups within science and engineering, and those who face obstacles of discrimination, are more likely to internalize failures as evidence that they don’t possess the capacity for success in these fields.

But mentorship and encouragement can transform the self-confidence and aspirations of prospective scientists.