Middle schooler creates sonar-enabled wearables to help visually impaired

We all navigate the world in our own unique ways. For people who are visually impaired, that often includes relying on sensory awareness in the forms of hearing and touch. Many aids exist to help the orientation and mobility of visually impaired people, although it is estimated that only two to eight percent of the blind and visually impaired use white canes or guide dogs.

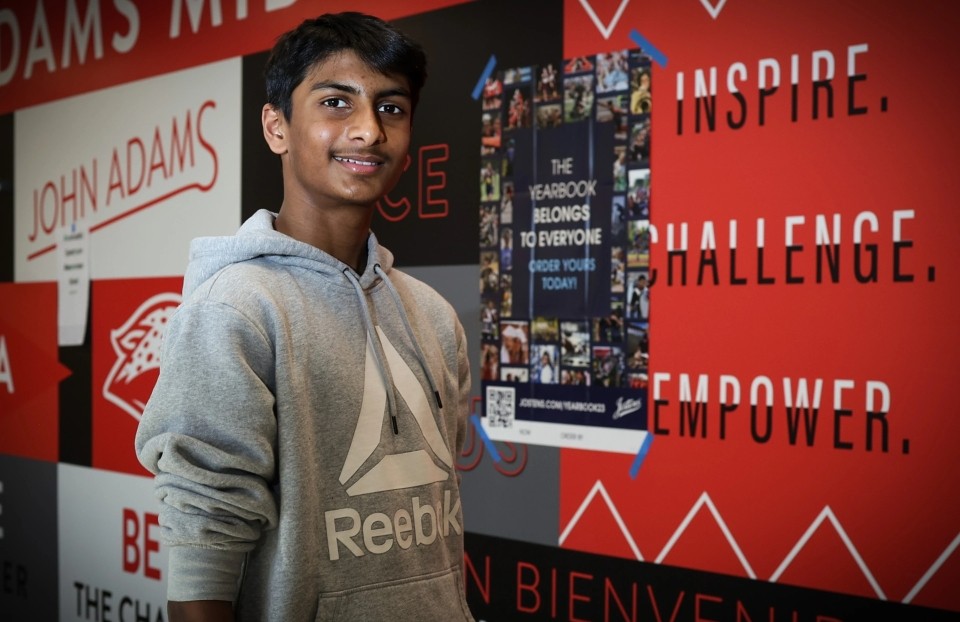

When a relative was diagnosed with glaucoma and told they could possibly lose their sight, Hill Holmes, a middle school student from Upper Marlboro, Maryland, sprang into action, asking: What could he do to assist his relative and low-vision individuals more widely?

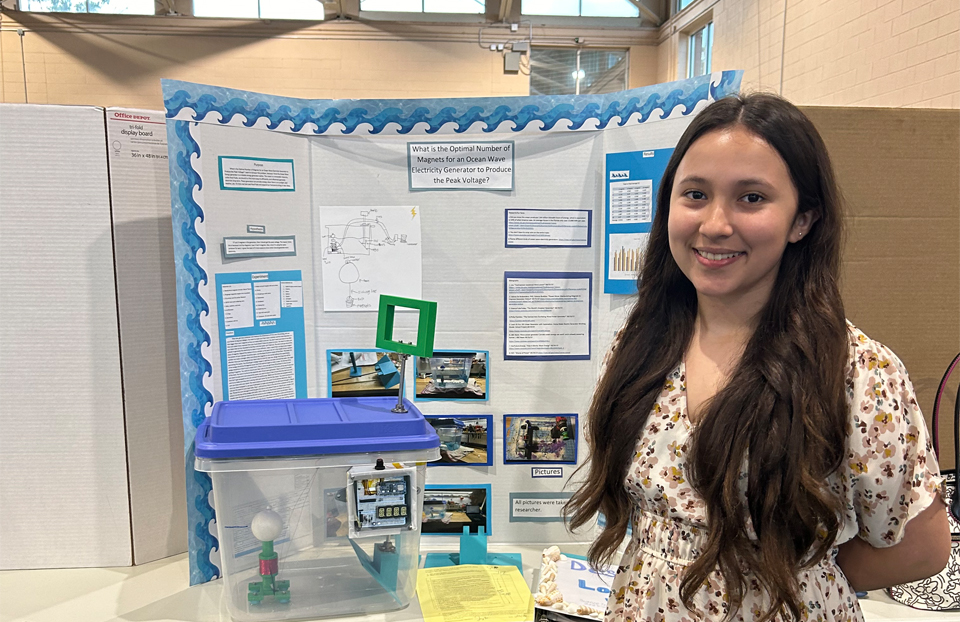

He zeroed in on the challenge of reducing injuries or inconveniences that can be sustained from colliding into unseen objects. In a project titled, “You Don’t See It, Now You Do,” Hill designed and created a wearable belt that issues an audible warning when the wearer comes hazardously close to a potential obstacle. Using sonar sensors and a small, programmable motherboard, the belt works by emitting frequencies too high for humans to hear, which then reverberate off nearby objects. Based on how long it takes the frequencies to return, the belt calculates the distance to the nearest object, and then creates an audible sound to alert the wearer. As the object gets closer, the tempo of the warning sound becomes more rapid.

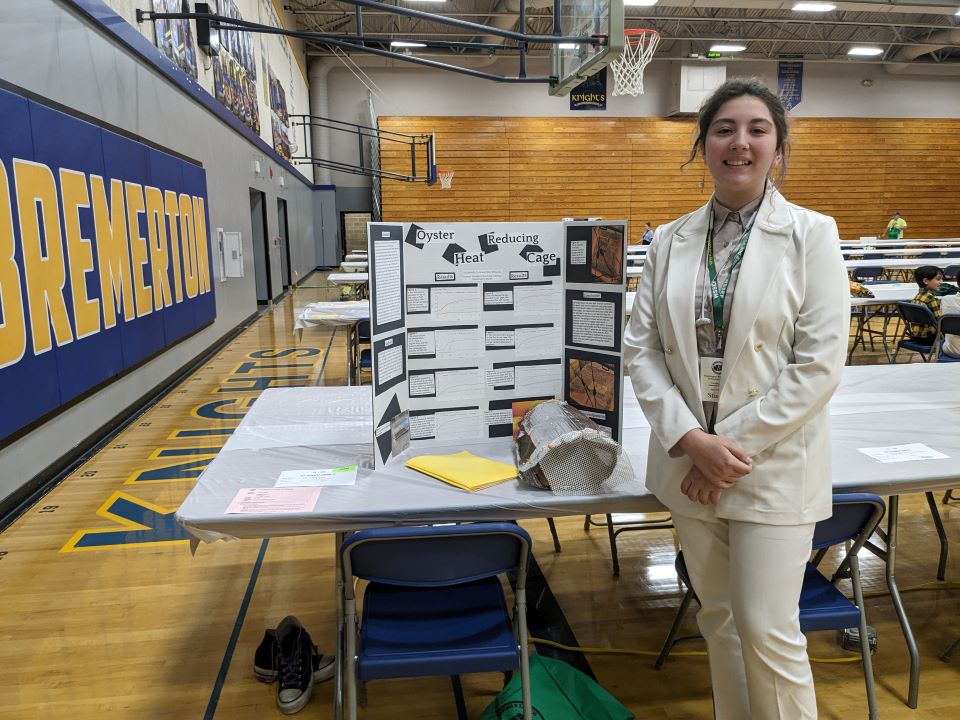

Hill tested his invention by blindfolding a few willing participants and challenged them to complete a 25-foot obstacle course, with randomly placed objects acting as hazards along the way. Over the course of his trials, it was clear that participants wearing his device collided with far fewer obstacles than those who were not. The results were promising, not only because the belt helped prevent collisions, but also because wearers did not need their hands or arms to operate it. This hands-free flexibility may make the invention even more valuable as an alternative or supplement to supports like white canes.

“My main goal is to empower the visually impaired,” said Hill. “I want to enable the user to feel confident in their travels, and for the user to be hands free if they choose.”

There were some challenges in the invention process, however. In some trials, the belt would sound a false alert when it detected users’ natural arm swings as they walked. To address this issue, Hill has embarked on a new iteration of the device.

His latest development is a sonar-enabled backpack, called the Eye Pack, that incorporates his technology into downward facing sensors located on the shoulder straps of the bag, which are high enough on the torso to avoid unwanted interference with swinging arms. With its innovative use of sonar technology to create a nonvisual aid, it is easy to forget the Eye Pack’s multifunctionality — with all its bells and whistles, it remains handy as a regular old backpack.

Hill was awarded the Lemelson Early Inventor Prize for his work. “Receiving the prize makes me realize that I am headed in the right direction,” said Hill. “Hopefully, I can inspire kids who are younger to want to become inventors and make our world a better place for all.”