ISEF alumna follows the ‘yellow brick road’ to human genetics

Defining moments come in all shapes and sizes. For Lauren Blake, being injured as a high school runner set her on a path to pursue science. She is now a Ph.D. candidate in Human Genetics at the University of Chicago, where she studies the relationship between human genetics and eating disorders.

During her freshman year at Hopkinton High School in Massachusetts, Lauren was mostly focused on her passion for running. She started running seriously at the same time her growth spurt began, which exacerbated underlying issues she had with her knees. To alleviate extreme knee pain, Lauren had surgery during her sophomore year of high school to remove scar tissue from both knees. With her running career disrupted, she looked for something else to fill her free time.

“I was fortunate that my high school had a science fair program. I was always interested in nutrition,” she recounts. One day at the grocery store, Lauren noticed that orange juice containers were usually stored under fluorescent light. With help from her school’s science fair coordinator, Lauren researched if storage conditions affect the Vitamin C content of beverages.

By junior year, Lauren was still participating in science fairs. At that time, her great-grandmother was in a nursing home and was susceptible to urinary tract infections (UTIs). UTIs are caused by an accumulation of bacteria in a structure of the urinary tract called a biofilm. Doctors recommended drinking cranberry juice, but Lauren was curious about other dietary sources that could help ease the symptoms. She delved into the tougher questions. What were the biological mechanisms of preventing these symptoms? While existing medical literature claimed that both cranberry and blueberry juices could ward off UTIs, the causal relationship was still unclear.

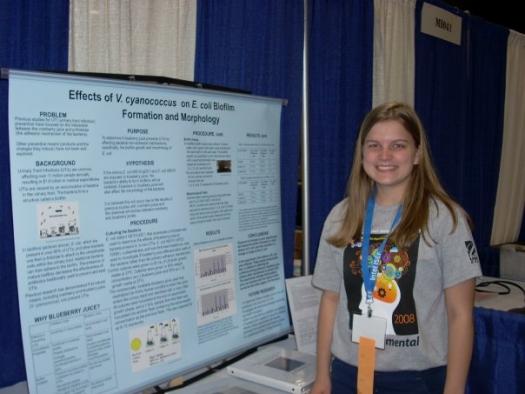

Coincidentally, there were researchers nearby at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute conducting such research. Without any prior connections, Lauren sent Terri Anne Camesano and Paola A Pinzon-Arango a research proposal and much to her surprise, they offered her assistance in designing a solid project and invited her to work in their lab over the summer. “It was a paid position! I never wanted to do anything else.” Ultimately, Lauren found that drinking blueberry juice does help prevent UTIs by inhibiting biofilm formation and changing morphology of detrimental bacteria.

That project earned Lauren a trip to ISEF 2008. “The passion there is unparalleled. It really opened my eyes, to meet great scientists around the world and witness the support and development that is available for the next generation of scientists,” she reminisced. After winning the Third Award in Microbiology, Lauren knew she wanted to attend a research-oriented institution for college.

During her undergraduate years at Duke University, she refined her scientific interests. She was encouraged by her mentor, Dr. Mariano Garcia-Blanco, to pursue a problem she cared about deeply and sought input from Dr. Margaret Humphreys, a historian, who wrote a book on yellow fever. “This was where my passion for genetics started to thrive,” she notes. With Dr. Humphreys’ insight and Lauren’s affinity for computational work, Lauren began investigating the biological underpinnings of susceptibility to the disease.

Given the limited number of programs that explicitly focus on human genetics, the choice of University of Chicago for her Ph.D. education was an easy one. Four years of genomics training later, Lauren asked herself what she wanted to spend the rest of her career on. Specifically, anorexia nervosa piqued her interest. “It’s a psychiatric disorder with the highest mortality rate, higher than depression and schizophrenia,” Lauren stated. Despite the disorder’s prevalence, research remains severely underfunded, motivating Lauren’s desire to call attention to it.

Lauren and her collaborators are using genetics to understand both susceptibility and treatment of eating disorders. She is currently exploring how biological factors, including gene expression levels, may be used to predict treatment response. These findings could be important for early intervention. “Anorexia nervosa is heavily stigmatized and for a long time it was believed that only environmental factors played a role.” She hopes the biological insights gleaned from her research can change the way people think about eating disorders and improve treatment options.

Her collaborators at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and the Eating Disorders Working Group at the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium recently collected DNA samples from over 16,000 individuals with anorexia. They found eight genetic variants correlated with susceptibility to the disorder, a number that is expected to increase as the number of participants in the study increase. Identifying these genetic variants only scratch the surface. Understanding exactly how these variants affect susceptibility and whether they are potential targets for intervention remain open questions—and something Lauren hopes to work on.

From her observations at the grocery store as a high school student to her current research at the University of Chicago, Lauren always found “doing science with a purpose” to be the most gratifying. Looking ahead to the future, her devotion is unwavering. “As long as the goal is treating eating disorders, I don’t care where that is, I want to be a part of it.” She has been funded by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship and the Genetics and Regulation training grant from the National Institute of Health.