Alumni, ISEF, Science Talent Search

Conversations with Maya: Feng Zhang

Maya Ajmera, President & CEO of Society for Science & the Public and Publisher of Science News, chatted with Feng Zhang, a Core Institute Member of the Broad Institute, a Professor at MIT and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. He is best known for his central role in developing CRISPR-mediated molecular technologies. Zhang is an alumnus of the 2000 Science Talent Search (STS) and the 1998 and 1999 International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF), both competitions of the Society. He is also a member of the Society’s Board of Trustees. We are thrilled to share an edited summary of the conversation.

You are an alumnus of STS and ISEF. How did these competitions impact your life?

Both ISEF and STS were very important experiences for me as I was going through high school. I grew up in Iowa, and even though I had a few friends in high school who shared my interest in science, it wasn’t like everybody shared my interests. Participating in ISEF opened up my view of the world, helping me to realize that there are a lot more people interested in science and technology. Meeting students from around the world, making new friends and instantly connecting with them gave me more confidence about pursuing science.

Participating in science fairs also gave me exposure to a larger breadth of science. It gave me an amazing glimpse of scientific areas that I wasn’t previously aware of, which reinforced my interest in science.

So you found your people, as they say?

Yes. A lot of the students I met through STS and ISEF became really good friends. By the time I started college at Harvard University, I already knew more than 50 other students who were going to be there because of my experience in these programs. And that was very special.

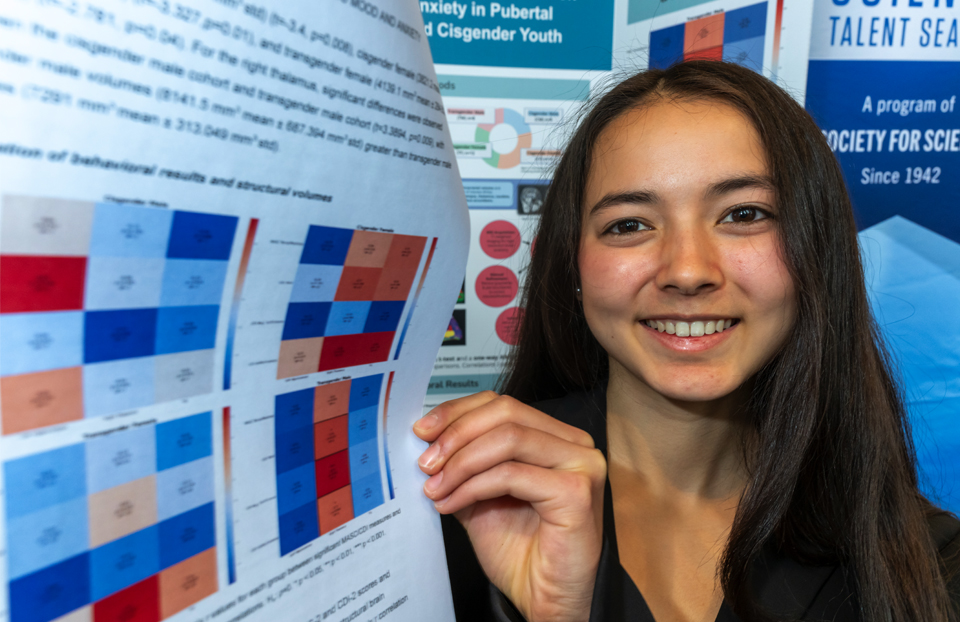

PHOTO COURTESY OF SOCIETY FOR SCIENCE & THE PUBLIC.

Let’s jump forward. You’re one of the pioneers of CRISPR gene-editing technology. Can you describe that journey?

One of the really exciting advances in biology over the past decade or two has been the completion of the human genome. As scientists started to understand more about how each part of the genome contributes to human health, the idea of being able to treat disease by going into our DNA and fixing it has become more and more tantalizing and urgent.

I was first exposed to genetics in high school when I was lucky enough to work in a gene therapy lab. Back then it was more rudimentary gene therapy, simply using viruses to deliver a gene that would kill cancer cells.

Later, I was excited to develop ways to modify DNA in our genome and started by working on systems that were new at the time, like zinc finger nucleases. Then I began to learn about the real challenges facing gene editing: our inability to correct different genes. When I first learned about CRISPR at a seminar, I got excited because I realized that it was something that could be customized to target a new gene.

So that’s how I got started. Since then it’s been really exciting to develop gene editing into a technology and see all the ways that scientists have creatively applied it, from understanding disease and biology to using it in agriculture to improve crops to turning it into a therapeutic. We’re continuing to develop the technology so that we can make people’s lives better and make the world a more sustainable place.

You and other researchers have called for a moratorium on human germline editing, which would create genetic changes that would be passed down to future generations. What are your concerns?

CRISPR is a very broadly applicable technology. You can use it in animal cells, human cells and plant cells to make changes to DNA and the potential for correcting DNA in somatic cells has really captured scientists’ imagination. These are cells in our body that don’t give rise to germ cells, meaning that people who receive gene-editing treatments in their somatic cells will not pass those changes on to their children.

The ethically challenging aspect has been the application of gene editing to germ cells, which are cells that give rise to eggs or sperm, or to directly modify newly fertilized embryos to change the DNA in the embryo. Those kinds of changes will lead to transmission of genetic changes to subsequent generations, which could have very large consequences for society.

CRISPR gene editing is still a new technology, and there are open questions about the efficacy or the specificity of the various CRISPR-based tools that are currently available. So technically there are a lot of challenges that prevent me from feeling comfortable using the technology in a human germ line.

Scientifically and morally there are challenges too. Scientifically, because the genome is so complicated, when you make one change it can directly impact other processes in the cell. That complexity makes it challenging to feel comfortable about the results being predictable when it occurs in the context of the developing embryo. And then ethically it is also very challenging because DNA changes could be passed on to future generations. This could have consequences on society or the human race as a whole, one of which could be exacerbated inequality.

I think because of all three challenges — technically, scientifically and ethically — it really is important to have a strong moratorium against the use of human germline editing until society forms a consensus regarding how and whether to move forward with the technology. Consensus doesn’t mean that every single person has to agree, but it does mean that society as a whole will have to have had a thorough and productive discussion around this topic.

You have an important role in academia, but you’re also an entrepreneur with multiple business ventures. Why do you think it is important to be a part of both worlds?

My parents instilled in me this idea that it’s important to do something useful for the world, and that’s the motivation that I bring to the things that I work on. Academic science is great for taking on high-risk projects and using outside-the-box approaches. So, within an academic setting, we can really explore new ways to solve a given problem.

But academic labs are not optimized for developing real-world products that can be directly used to benefit patients’ lives. That stage is much more suited for industry. It’s very expensive to hire experts, run clinical trials and set up large manufacturing processes, and there are more financial resources that are available in industry. Being able to take laboratory research and then expand that into an industrial-scale R&D process is really important for turning laboratory discoveries into useful solutions.

What advice do you have for young people just starting college?

When I was finishing high school and getting ready to go to college, one of my high school teachers gave me a piece of advice that I want to pass on. He said, “When you get to college, figure out who the best teachers are. It doesn’t matter what the teacher teaches. Go and take a class with him or her, and you will open up your mind to thinking about many more interesting problems.” I took that advice to heart, and it was really the best advice that I could have received. When you encounter a good teacher who can share their passion and excitement for a given area, they can infect you with the same passion.

And what about people who are starting their professional careers? Any advice around that?

As one starts on a professional career, I think it is equally important to find good mentors; someone you can learn from and who will take an interest in helping you develop your own abilities. It also means that you have to be willing to be mentored and keep an open mind.

What books are you reading right now? And what books inspired you when you were young?

This week, I’m reading Blink by Malcolm Gladwell. When I was young, I read a lot of science fiction, but I think the one that probably was most inspiring for me was actually Jurassic Park. That really got me excited about the potential of molecular biology.

There are so many challenges in the world today. What keeps you up at night?

I think one of the biggest challenges that we face today is climate change, and I think there are a lot of things that we should be and need to be doing to mitigate the potential negative consequences of climate change. That is something that I hope more and more people will start to realize and act on. CRISPR is actually one of the tools that I think can help a bit, particularly in agriculture and the global food supply. Scientists are working on creating more drought-resistant crops, as well as crops that need less water or require fewer pesticides. This could both create a more resilient food supply as our climate changes, while reducing some of the pressure that modern agriculture places on our environment.