Babies, Parenthood, and Science

Kim Scott (Intel STS 2006), a Cambridge-based research scientist and mother of two, has always been passionate about science, math, research, and babies. Her childhood passions have now merged into an academic career studying childhood development at the MIT Early Childhood Cognition Lab.

In high school, Kim attended the Research Science Institute at MIT, a program that welcomes the world’s most accomplished students every year. She also participated in Intel STS in 2006, and said she still stays in touch with some of the alumni of the competition. Kim proceeded to receive her B.S. in Engineering & Applied Sciences at Caltech and then received her Ph.D. in Brain & Cognitive Sciences at MIT.

As a teenager, Kim liked to babysit and loved her younger charges. She watched and learned from her stay at home mother as she raised her sisters and her. Her father, an experimental physicist at MIT, also served as an inspiration in her career. She learned from him that “… if you have a question, design an experiment and get nature to tell you the answer.”

I can’t think of any better system to study then childhood development to understand the human species and the world at large.

And that she has. Kim is founder of an online cognitive psychology platform called Lookit – an online database for childhood development and baby behavior data. The platform allows collecting data in infant and child behavior easier for parents and researchers alike. She’s long been interested in understanding ‘how can you tell what a baby is experiencing?’

“They can’t do much at all when they’re born. They can’t even control their arms to reach for things,” Kim commented. “But they’re not just blank slates – they come prepared with expectations about how the world ought to work, and those expectations can teach us about how the mind works. I can’t think of any better system to study then childhood development to understand the human species and the world at large.”

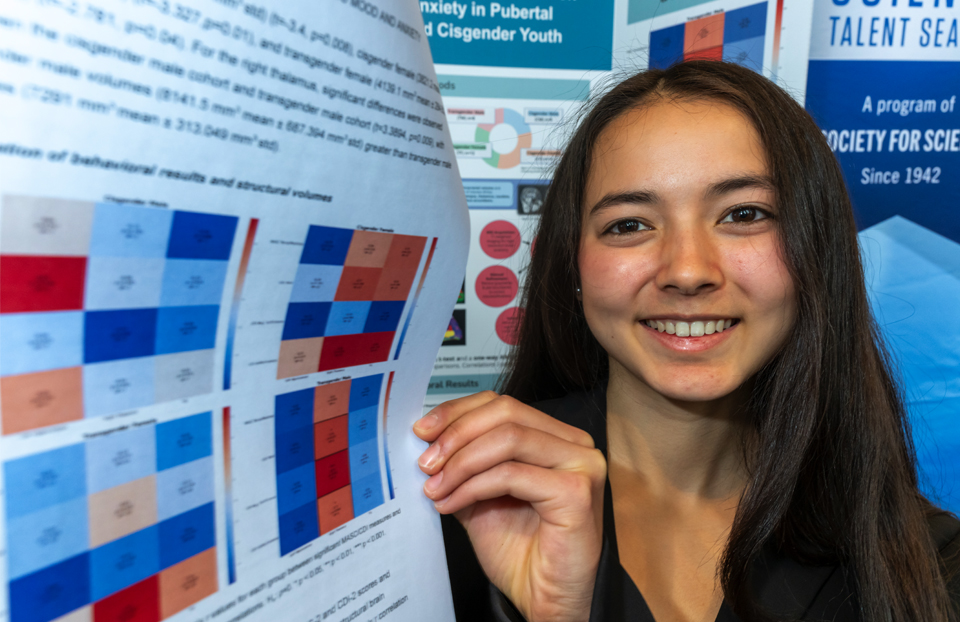

Kim Scott and her daughter, using Lookit.

As working parents, Kim and her husband know what it means to be busy. They have two children, an eight year old boy named Remy and a one year old daughter named Zenna. She knows firsthand that it’s difficult to get people into the lab with small children. Kim’s online lab, Lookit, enables researchers to collect larger sample sizes while experiments can be done in front of a home webcam. It’s opened up a number of avenues for research to be collected, shared and managed most effectively.

If you have a question, design an experiment and get nature to tell you the answer.

One of the Lookit experiments focuses on the psychological concept of “preferential looking” – which of two things does the baby choose to look at. “It’s been shown that babies prefer to look at people who are smiling rather than someone who is angry,” Kim explains.

“Babies recognize their mothers faces from pretty early on. They also recognize their father, but it’s about who they are spending the most time with. They will recognize both parents,” said Kim.

As a scientist and a parent I am amazed by how much they can figure out the world.

Kim said one of her most pivotal experiences was when she realized that, “it was valid to study the mind and consciousness. A question that kept me up at night.” In her undergraduate years at Caltech, she took a class taught by renowned neuroscientist Christof Koch, a neuroscience researcher who showed her that behavior, childhood development and consciousness could be treated as empirical questions.

Kim’s says her larger goal is to launch Lookit so it can support research that will help families and parenting. She wants the platform to be an openly accessible tool that researchers can use to answer behavioral questions with more data.

“As a scientist and a parent I am amazed by how much they can figure out the world. They can make rich inferences from very sparse data. It is amazing to witness- when they are very little babies they aren’t doing much, but you know there’s somebody in there.”

Thanks to Kim and other researchers in her field, we’re beginning to understand the more complex questions surrounding the science of parenting.