A middle schooler’s mission to clean up the world’s water

For the fourth year, The Lemelson Foundation is giving $100 awards to outstanding young inventors in Society Affiliate Fairs with middle school participants around the country. The prize was especially created to reward young inventors whose projects exemplify the ideals of inventive thinking by identifying challenges in their communities and creating solutions that will improve lives.

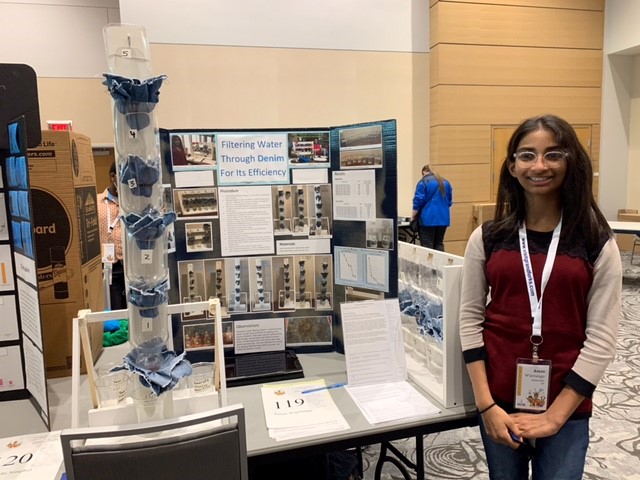

Over 2 billion people worldwide lack access to clean drinking water, a serious global problem resulting in disease and even death for hundreds of thousands of people every year. Most people might look at a problem of that magnitude and think there isn’t much they can do to help, but middle schooler Amaa Wijetunga thinks her research and working together might mean there is hope.

When Amaa, now a sixth grader, at South Middle School in Grand Forks, North Dakota, began to learn about the issue of polluted drinking water, she sprang into action.

“I really wanted to help these children to have access to clean water,” said Amaa. “I realized that creating a major filtration system for the whole community would be beyond my capacity for the time being. Therefore, I’d focus on creating a very simple water filtration system that even a child would be able to make by themselves.”

Though she set out to create a water filtration system that was simple, the process of invention proved to be complex. With a goal of filtering water to under five Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU), a measure of the presence of suspended particles in water, and a guideline for safe drinking water by the World Health Organization, Amaa tested many different materials for their filtering capabilities. From sand, foam, ground and sieved charcoal to t-shirt fabric and coconut fiber, Amaa tested many materials to discern what readily available material would be most effective as a potential filter.

When her initial trials showed that the t-shirt fabric yielded the most promising results, she saw an opportunity for further investigation—could another common household fabric filter dirty water even more effectively? She left no stone unturned, or no fabric unsoaked. After filtering more dirty water through silk, denim, cotton, fleece, microfiber, polyester and other materials, she found a new most promising candidate: denim.

Looking at the denim sample through a microscope, Amaa hypothesized that the material’s tight-knit structure might be responsible for its effective filtration. Just as importantly, she reflected that the ubiquity of denim, even used or recycled clothing, could make it all the more viable as an easily replicable filtration system. Now it was time iterate and refine how the system would be constructed.

To create the system, Amaa cut the bottoms from five empty juice bottles and affixed denim filters to the spout of each bottle. She connected the five bottles in a vertical tower, allowing water to trickle down, filtering through all five layers. She experimented using varying numbers of levels in the tower, different quantities of denim layers over each spout and using new versus used denim samples to find an optimal filtering apparatus. To test the samples, she partnered with her local regional water treatment plant to test the turbidity of her samples and find which came closest to her goal of five NTU or less.

Through her testing, she determined that the best results were achieved using six or more layers of denim, and she also found that old denim, somewhat counterintuitively, was more effective than new denim. This, she hypothesizes is because dyes from new denim can seep through the filters and into the samples. After her latest round of experimentation, her filtration system came very close to the drinking standard of five NTU. And she’s not done yet. Her next goal is to further improve the system by devising a way to remove bacteria from the filtered water using natural resources.

For her work, Amaa was awarded a Lemelson Early Inventor Prize at the Northeast North Dakota Regional Science and Engineering Fair in Grand Forks. On receiving the award, she reflected, “It encourages me to continue using science to serve people in need.”

We look forward to seeing what innovations Amaa develops next.