Studying the role of copper deficiency in heart disease

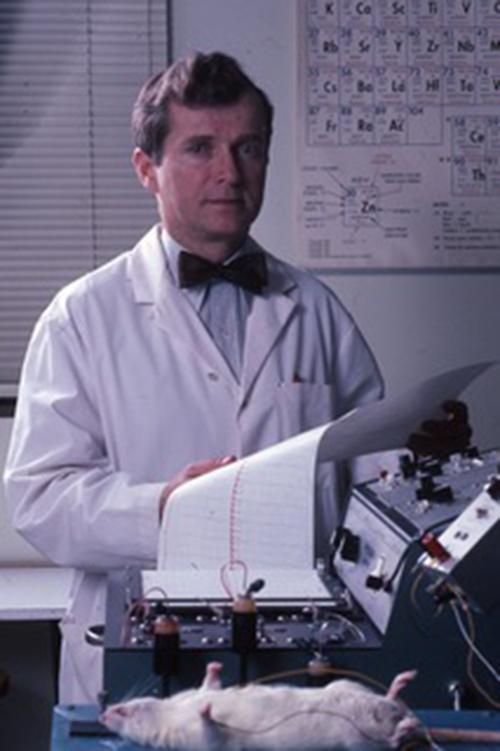

Leslie M. Klevay, M.D., S.D. in Hyg., has been studying the effects of copper on the heart for decades. The professor emeritus of internal medicine at the University of North Dakota researches the leading cause of death in the Western world — ischemic heart disease.

“It’s the leading cause of death. It’s important,” said Dr. Klevay, an alumnus of the 1952 Westinghouse Science Talent Search (now the Regeneron Science Talent Search). “If you want to work on something in science you don’t want to work on something trivial.”

If you want to work on something in science you don’t want to work on something trivial.

As a graduate student at the Harvard School of Public Health, Klevay was immersed in research on dietary fat. He was attracted to trace elements because he noticed a paper showing if a person lived where the drinking water was hard, there was less chance of heart disease than if a person lived where the drinking water was soft. This phenomenon was first discovered in 1957 in Japan, and has since been confirmed numerous times, he said.

Klevay became a faculty member at the University of Cincinnati Department of Environmental Health, and built a laboratory to study trace elements that might relate. Copper was easy to study and fulfilled some of his thinking about a potentially protective agent for heart disease.

“Lo and behold, I discovered and published in 1973 that you can raise cholesterol of rats substantially by making them deficient in copper,” Klevay said. “My whole career has been built around this puzzle of hard water, and then the discovery of copper deficiency and cholesterol.”Society alumni like Dr. Klevay are at the forefront of crucial research. Support them by becoming a member.

Copper deficiencies have long been a known culprit in heart disease seen in domestic animals, but no one had linked the findings to humans. Klevay has been searching for evidence that his results can be generalized to the wider world of medicine and public health.

“It seems to me, in heart disease, nobody looks at the whole elephant,” Klevay said, referencing a poem about six blind men inspecting different parts of an elephant and not knowing what exactly they are facing as a whole. “People have been preoccupied with dietary fats. Lately, they’re getting back to sugar again.”

Klevay recently published a paper showing the anatomical, chemical, and physiological similarities between animals deficient in copper and people with heart disease. Cholesterol and glucose intolerance are well known as predictors of heart disease (and he has shown that people with depleted copper respond to deficiency with increased cholesterol, in a 1984 paper, and higher glucose, in a 1986 paper). But high levels of uric acid, a chemical created when the body breaks down purines (which can be found in foods and drinks), can predict heart disease as well or better than cholesterol levels. “Everyone says lower your cholesterol to prevent heart disease, no one says lower uric acid — I don’t understand why,” he said.

Smaller babies, increased uric acid, hearing loss, and lower cholesterol in the summer can be explained by the copper deficiency theory, but not by any other theory, Klevay explained. “These are among the 80 similarities explainable by this theory,” he said.

It seems to me, in heart disease, nobody looks at the whole elephant.

Lately, he also studies the phenomenon that hard drinking water can protect against heart disease. Even without working in a lab anymore, Klevay has nearly completed another manuscript and plans to send it to a journal. In his upcoming paper, he proposes that bottled water may be unhealthy because it is too pure. Klevay researched the hardness of bottled water and matched it with water quality criteria from the U.S. Geological Survey. Two-thirds of 33 different bottled water products were soft, none were hard, and seven were very hard. Water hardness is defined in terms of calcium and magnesium. He went further, using a Canadian database of 25,000 foods, and found that beer and wine are hard water.

Perhaps the water hardness in beer was the mysterious ingredient that improved copper deficiency in my rats.

“I tied these data to my most fun paper,” he said, which was published in 1990, when he let rats drink beer. Copper deficient rats that drank beer lived six times as long with heart damage and lower cholesterol than rats that drank water. Those that drank the same amount of alcohol and water experienced no benefit. Beer improved copper utilization.

“Perhaps some of the benefits of beer and wine for heart disease are because of hard water,” he said. “Perhaps the water hardness in beer was the mysterious ingredient that improved copper deficiency in my rats [in my previous study].”

The advice Klevay offers young people interested in science: Read great literature to learn how to write and don’t use acronyms. Also, read the history of science, the original articles, to learn how to think. He also said that medical school can be a great liberal arts course for medical research.

At the 1952 Science Talent Search, Klevay remembers meeting President Harry Truman and Harlow Shapley, an astronomer and one of the judges. “He was the first real scientist I ever met,” Klevay said.

He also learned how to tie bow ties for the gala in 1952, a skill which he continues to use to this day. Bow ties don’t get pulled on by children and they don’t dip into chemicals in the lab.

Klevay has tried to increase interest in the Science Talent Search in Grand Forks, North Dakota. The local high schools post notices about the competition on bulletin boards, but it’s not enough. “I think about the Bronx High School of Science and Evanston High School in my old neighborhood near Chicago. I’ve been telling people around town if a nun in Marshfield, Wisconsin can produce seven winners in eight years, we can put Grand Forks on the map,” he said. “I would not have been in the contest had it not been for an outstanding high school chemistry teacher and a high school principal in Milwaukee who told me about it.”

Learn how to write and don’t use acronyms.

Since 1952, the Science Talent Search has grown and changed. Klevay did most of his project on his back porch, where three of his double-yolked eggs hatched two chickens; now, many students complete research in university laboratories. The Science Talent Search’s monetary prizes have also increased since Klevay competed. “I got a hundred dollars,” he said. The grand prize today is $250,000.