Persistence, resilience, and adaptability: The qualities of a scientist

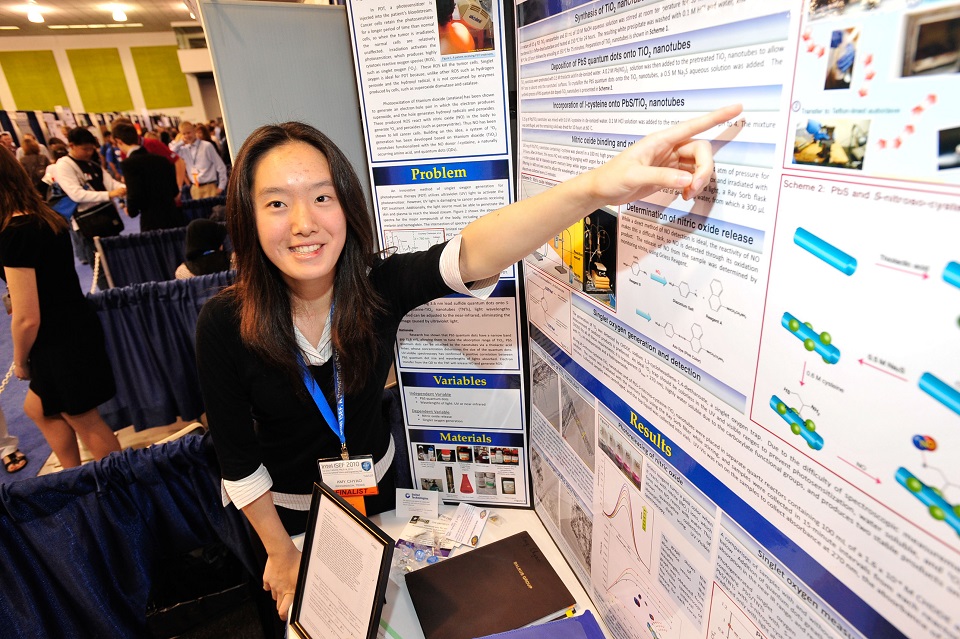

How many chances are you given to ask questions of a Nobel Prize and science award-winners? At the Excellence in Science and Technology panel on Tuesday, the Intel ISEF 2016 finalists were given that opportunity.

The esteemed panel included: J. Michael Bishop, who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1989; Martin Chalfie, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2008; Elissa Hallem, who won a MacArthur Fellowship in 2012; and Cato Laurencin, who won the National Medal of Technology and Innovation in 2016.

J. Michael Bishop, a Professor in the Microbiology and Immunology department at the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, won the Nobel Prize jointly with Harold E. Varmus for their discovery of the cellular origin of retroviral oncogenes. Martin Chalfie, a professor at Columbia University, won the Nobel Prize for discovering and developing the green fluorescent protein, GFP. Elissa Hallem, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Microbiology, Immunology, and Molecular Genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles, is a neuroscientist who studies the physiology and behavioral consequences of odor detection. Dr. Laurencin, the Endowed Chair Professor in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at the University of Connecticut, works on repairing ligaments and musculoskeletal tissues.

Martin Chalfie convinced himself that he shouldn’t study science because he spent one summer in a lab and none of his experiments worked. After graduating from college, he taught high school for a few years. Then, he worked in a lab again and this time the experiment worked. “It gave me the confidence to go to graduate school,” he said.

The most important quality for scientists are persistence, integrity, loyalty, having an open mind, being a hard worker, courage, resilience, and adaptability.

“Experiments don’t always go the way you want,” Elissa said. “You need persistence to keep adapting to changing circumstances.”

She also mentioned embracing differences. “That’s what makes us unique and good scientists,” she said.

The panelists assured the Intel ISEF finalists that by making it to the science fair, they had already proven they had the skills to succeed in college. But they encouraged them to learn how to ask questions and listen.

Creativity plays a key role in science. “It’s at the core of what we do,” Michael Bishop said. “Science without creativity, without imagination, is totally inert. It doesn’t work.”

To be an effective science communicator, use simple vocabulary and don’t use scientific jargon.

“Think of examples from everyday life,” Michael Bishop said. “Use similes and metaphors that [an audience of lay people] can relate to. And do your best to correct misapprehensions.”

When explaining research, scientists shouldn’t fall into the pit of explaining all of their data. “When people want our conclusions, they want to know what we’ve learned. Humor doesn’t hurt either,” Martin Chalfie said.

The most important thing is judging who your audience is, Elissa Hallem said. “I explain something very differently to a colleague than I do my kids or an adult. If someone follows up then I provide details,” she said.

“As you have more success in science, you will be talking to a more general audience,” Cato Laurencin said. “This is because your science has more impact.” He encouraged the finalists to explain their motivation and the human side of their research.

If the panelists could bring one futuristic technology into existence, they chose:

- Michael Bishop: Technology that allows us to detect every form of human cancer at its earliest possible stage.

- Martin Chalfie: A way to test drugs that didn’t cost millions of dollars.

- Elissa Hallem: CRISPR is pretty close to her future technology. It has so far worked on every organism. The ability to take tech and ultimately apply it to humans would be a huge advance.

- Cato Laurencin: A limb regeneration machine.

The biggest impediment to science today is the conflict people have among each other, according to the panelists.

“In the entire world we’re using our resources for conflict rather than science,” Cato Laurencin said. “The conflicts we have as people of the world really limit our ability to go to the next level in science.”

Elissa Hallem also mentioned the lack of understanding of the value of basic research. “The public has to understand that new insights can come from all types of research, not just medical research.”

The panelists also explained that a new era of science seems to have dawned called convergence. Different groups of researchers can come together to work and solve problems.

Many breakthroughs in the past were made by individuals, but Michael Bishop said there is room for both approaches. But don’t discredit the power of the creative individual, he said.

Diversity is also critical in STEM fields and for the progress of science. “I think it’s a great time to be a woman doing science and engineering,” Elissa said. “We need to support different types of people doing different types of work. It’s important for students to see people like themselves in a leadership position.”

View low points and challenges as opportunities, the panelists said.

“There are tons of challenges that take place during your life,” Cato Laurencin said. “The bigger the challenges, the greater the opportunities.”

He offered a Zimbabwean proverb: “To stumble is not to fall, but to walk faster.”

To inspire the next generation into science, high school students and Intel ISEF finalists can volunteer in their schools and communities, the panelists said. Volunteering makes a huge difference, Elissa said.

“In a lot of schools, the captain of the football team is the rock star. But actually, you all are the rock stars,” Cato Laurencin said, addressing the room full of Intel ISEF finalists. He encouraged the finalists to have their schools put up exhibits of their work. “If you do that, you’ll inspire a lot of young students.”