Alumni, Regeneron STS, Westinghouse STS

Passing a love of science through generations

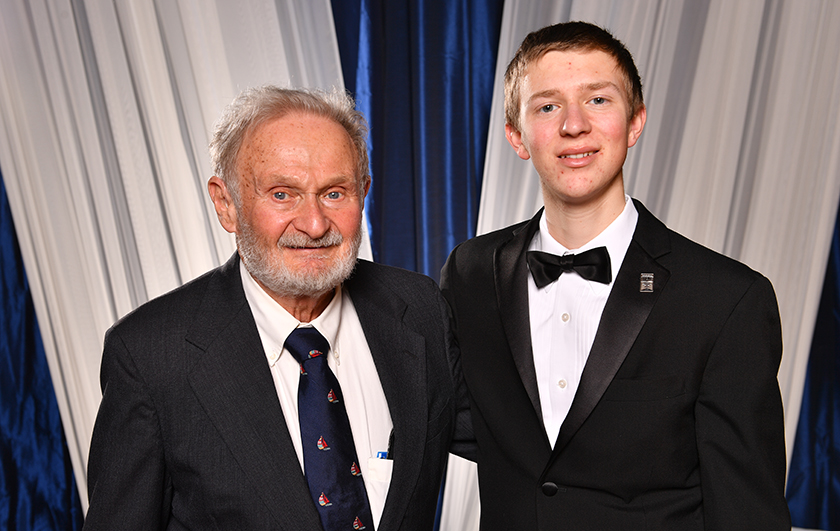

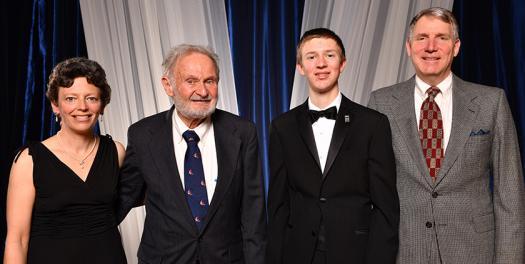

Sometimes, the love of science threads its way through the generations of a family, like inherited traits of DNA or lines of code from a cascading style sheet passing on rules to others. This is especially the case for Aaron Yeiser, who won the second place award at the 2017 Regeneron Science Talent Search. His grandparents and father work in computer science, technology, and chemical engineering.

Aaron and Frank designed techniques to solve complex math equations more efficiently.

“I was encouraged to pursue a STEM career because of Papa,” Aaron said. His grandfather Frank Sandy was a Science Talent Search finalist in 1954, when the competition was sponsored by Westinghouse.

“Aaron’s been doing very well in science and math, so I won’t say I was surprised,” Frank said of Aaron becoming a Regeneron STS finalist. “I was delighted by not only that, but his getting early-action admission to MIT, which happened just a couple of days after my wife died. She would have just been so thrilled.”

“I’ve been very impressed by the things he’s built,” Frank said of Aaron’s interest in drones and other STEM activities.

Frank, a computer programmer, was also introduced to his STEM field by a family member. “My late wife was the one who got me into computer programming,” he explained. When he was working on his Ph.D. thesis, Frank asked his wife to help with data reduction. “I kept looking over her shoulder to see what she was doing, and thought that that was really fascinating,” he said. He went into computer programming from there.

Aaron has always been interested in math. Differential equations came along when he applied to the MIT Primes USA program, a mathematical research program for high school students.

Don’t blow off English class, because good communication is just as important as your actual research.

Current methods of doing numerical simulations are very inefficient when trying to get precise results. “So I developed a new method that is a much more efficient way to get precise results,” Aaron said. His algorithm has applications in fluid dynamics and precision computing in physics. This could lead to better airplanes and possibly better artificial heart pumps, he explained.

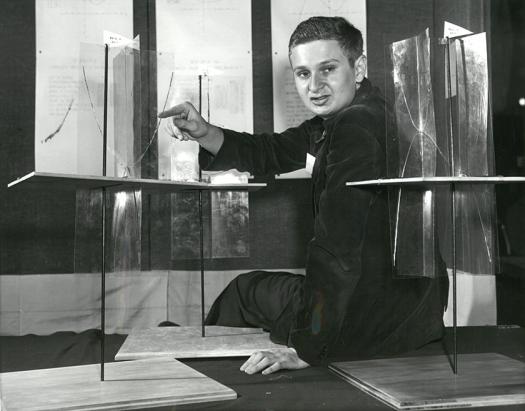

For his 1954 STS project, Frank focused on new methods for solving complex cubic equations. There is a very nice formula for quadratic equations that people learn in algebra. But “for cubic equations, there is nothing nice,” he said. There was a “horribly complicated” method that Frank couldn’t understand. So he created his own technique.

“I’ve been interested in science all my life,” Frank said. “Even in elementary school I played around with electrical wiring and had my bedroom all wired up with batteries and light switches attached to my bed. It was a lot of fun.”

Frank worked at Raytheon, creating computer models of various devices. He became more interested in the programming rather than the physics of how the devices worked.

Aaron encourages others who are interested in STEM to look for any opportunity to get involved in research, like through universities or professors. And “don’t blow off English class, because good communication is just as important as your actual research,” he said.

It’s encouraging that in the future I might be working with some of the other finalists.

“Just keep plugging away at it,” Frank agreed. “Spend a lot of time reading, [do] whatever experiments you can do, if you’re experimentally inclined as opposed to if you’re a theoretician, go do them.”

When asked for his most memorable experience as a finalist, Frank laughed and reflected on the changing nature of technology. Back then, all of the official communications for STS were sent through telegrams. “Before the Science Talent Search, I’d never sent or received a telegram,” he said. “That’s the way they notified winners in those days. The web didn’t exist, telephones didn’t have answering machines, so they sent out telegrams.”

“When we got to Washington, we had to send ‘safe-arrival’ telegrams to our parents to let them know that we had gotten here,” he explained. “And I’ve never sent or received a telegram since then.”

Before the Science Talent Search, I’d never sent or received a telegram. That’s the way they notified winners in those days.

Aaron was inspired by meeting other young students at the Regeneron Science Talent Search who were also interested in STEM and were working on diverse research projects. “Everyone has an interesting story to tell,” he said. “It’s encouraging that in the future I might be working with some of the other finalists.”