Alumni, Science News for Students, Young & Amazing

Our favorite teen research stories from Science News for Students, Pt. 1

We’ve seen some incredible teen scientists in 2017. This year, Science News for Students (SNS) reported on student scientists who are inventing better ways to detect blood type, buoys to alert swimmers of deadly rip tides, and more.

Check out these amazing stories from writers Bethany Brookshire and Sid Perkins. This is Part 1 in a series, with stories from Sid. We’re giving you five today and five Monday to feed your curiosity.

Detecting failing underground pipes through vibration

Sanjay Seshan (Broadcom MASTERS 2017) identified a way to detect damage in water pipes, even those buried underground. U.S. water-delivery systems lose some 2 trillion gallons of water annually, equal to the water needed to fill 25 billion bathtubs or to provide every person on Earth about 270 gallons of water each year. In poorer nations, the problem can be much worse. Sanjay used lengths of PVC pipe and attached a tiny but powerful speaker to the outside. He also attached two small microphones to the pipe. He put one near the speaker and another farther away. He used a computer program to send electrical signals to the speaker. After measuring how well a healthy pipe transmitted each sound pitch, Sanjay damaged the pipe and ran his tests again. The pipe’s sound transmission changed. His technique may mean pipes can be rigged with sensors and then monitored over long periods. It might even work on bridges that vibrate differently if some of their parts have cracked.

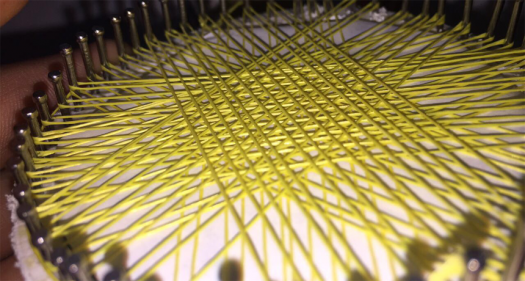

A better way to stop a bullet

Lucas Lynn (Intel ISEF 2017) studied the effectiveness of bulletproof fabric, a crucial safety equipment for police officers and military troops. He found that the fabric in body armor could work better if it were woven differently. The most common forms of body armor, including bulletproof vests, are woven from a super-strong plastic fiber called Kevlar. These fibers in body armor typically run in two directions and cross at 90-degree angles. By changing the fabric’s weave to intersect at 60-degree angles, the mesh has triangular holes instead of square. And the holes tended to be smaller and the weave tighter than the 90-degree version.

Buoy warns of deadly rip currents

Maddison King (Intel ISEF 2017) invented “Clever GIRL,” a buoy that lights up when waters have dangerous currents. Maddison, also a lifeguard, created the Clever Global Intelligent Rip Locator to alert swimmers to potentially deadly waters that have rip currents. It can be secured to the ocean floor, or attached to others by a long chain. Water flowing past the buoy drives a small propeller, and water traveling faster than 70 centimeters per second spins the propeller fast enough to trigger a warning light atop the buoy. Because the spinning propeller powers the warning light, her buoy needs no batteries. The current prototype cost Maddie about $300 to make. But if the devices were produced in large numbers, they might cost no more than $100 each.

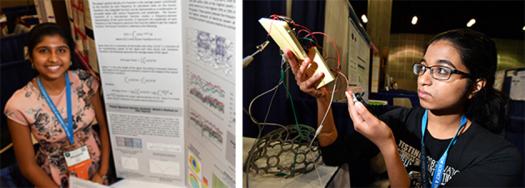

Detecting epileptic seizures

Neha Hulkund and Maanasi Garg (Intel ISEF 2017) both, separately, analyzed brainwaves to find early warning signs of seizures. Patterns in brainwaves may signal an oncoming seizure — with time to take protective action, data by the two teens suggest. Neha focused on brainwaves recorded in five patients, analyzing 30 seconds to five minutes worth of pre-seizure data. She trained a computer to look for brain-activity patterns before each seizure. Maanasi looked at brainwave patterns from eight patients. She used statistics to compare patterns recorded before and during seizures with patterns during normal brain activity. She only looked at brainwave patterns recorded in the 30 seconds leading up to a seizure.

Neha’s method appears to predict impending seizures three minutes before they occurred, with 96 percent accuracy. If a 30-second warning is all that’s desired, the method would be more than 99 percent accurate. These warnings could come from a small electronic device a patient might wear.

A needle-free way to detect blood type

Zainab Alnakkas (Intel ISEF 2017) showed it’s possible to discriminate between different blood types using infrared light instead of blood sampling. In the future, she said, this may mean nurses or lab workers could simply shine a light into your skin — and analyze the light that reflects back — to know which blood donation would be right. This low-cost method wouldn’t even require needles.