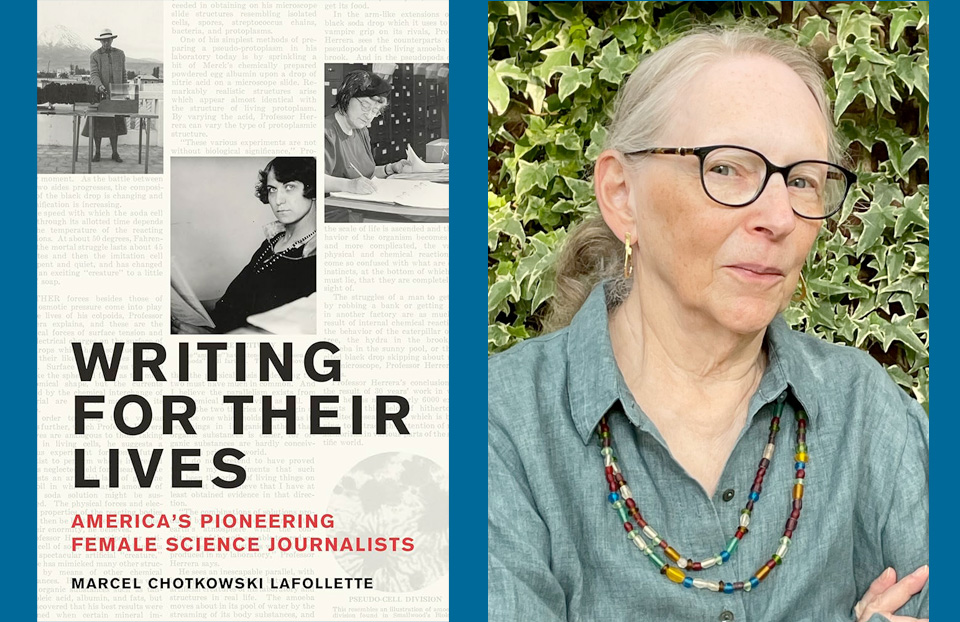

Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette and the pioneering female journalists who helped to shape Science News

“None of these women set out to be science journalists.”

So began Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette during a recent webinar hosted by Science News and MIT Press on her book Writing for Their Lives: America’s Pioneering Female Science Journalists. Marcel, a historian and author, uncovered the untold stories of eight female science journalists who helped pave the way not only for other women in journalism, but also made significant contributions to science journalism in general. This was a special event for Science News, as the trailblazing journalists discussed in the book were reporters for Science Service, which would later become Society for Science, publisher of Science News.

An independent historian and research associate at the Smithsonian Institution Archives, Marcel has spent years researching science journalism and written books on the Scopes trial as well as covered science on both radio and television. Her most recent book dives into the lives of the female journalists of Science Service, and in doing so explores their role in the founding of science journalism itself.

On Wednesday, November 15, Marcel joined Science News Executive Editor Elizabeth Quill and viewers to answer questions on her new book and to share just a small slice of the history of the journalists she chronicles in the book. Like all the best historians, Marcel clearly cares about her subjects as both historically significant figures and as individuals, offering glimpses into their rich and exciting personal lives through postscripts and asides found in their correspondence. She describes with tenderness the risks, setbacks and triumphs of these journalists as they took on two male-dominated worlds at once: science and journalism.

At the time of its creation, Science Service was intended to combat misinformation and pseudoscience through accessible and straightforward science journalism, a goal carried forward today. In the face of prevailing skepticism and distrust toward science, this goal remains as urgent as it was at Science Service’s founding and is buoyed by the precedent set by the steadfast journalism and sense of curiosity fostered by the female journalists Marcel describes.

As Marcel writes you can picture a young Emma Reh, her marriage beginning to unravel, setting out for Mexico to be a stringer for Science Service and other news services, charting her own course in the newly unfolding world of science journalism. What began as one year turned into eight, and through studying Emma’s journalism and her correspondence with colleagues and friends, Marcel was able to learn how Emma fell in love with the culture, the people and the archeology of Mexico and become an incredibly skilled and trusted reporter on archeology. Emma’s correspondence, along with the correspondence of other female journalists at the Science Service, helped Marcel to understand what it was like to be a woman making a living through journalism at a time when financial independence was still out of reach for so many women.

At the time these women were working for Science Service within the field of science journalism. The world of science had a high bar for entry, and for many who were already part of the club, this meant information shared with the public should be limited. However, these women were determined to make scientific discovery accessible to the American public, especially on issues that impacted their readers like health and medicine.

Marcel explained in her talk that “all these people, Jane, Emily, and their colleagues all shared in common a love of science, love of writing, and a real desire to communicate what they were learning about science to members of the public.”

By leading with empathy and respect for their readers, these pioneering journalists were part of the democratization of scientific discovery and innovation.

In her book, Marcel paints a vivid picture of the late 1910s and early 1920s. During this time, women’s suffrage top of mind and the evolving rights of women in the workplace introduced unthinkable opportunities that were previously unimaginable. This changing climate dovetailed with the serendipitous hiring of Edwin E. Slosson as Science Service’s first news director, a man who just so happened to be married to a suffragist and was himself a strong supporter of women’s rights. Edwin found himself needing to build a newsroom, and to do so opened his door wider than those before him had.

“[Edwin] said, if you can write … and you’re interested about science, then I’ll hire you or at least give you a chance,” Marcel explained. “And this was an unusual opportunity for young women [and] women in science who wanted to write about science.”

This open door brought in Jane Stafford, who was born into a wealthy Chicago family and attended Smith College where she fell in love with science and medicine. After graduating she worked for the American Medical Association before finding her way to Science Service where she reported on medical innovations. She would eventually become one of the premier medical journalists in the country. As a young journalist, she was determined to cover the issues her readers found relevant regardless of their perceived “propriety,” including the newest research on venereal disease and pregnancy.

Through her research, Marcel not only discovered the breadth and depth of the reporting these women undertook, but also gained a sense of the relationships between them and what working in the Science Service newsroom must have been like for these women. When describing the correspondence she found, Marcel remarked on the humor these women shared, as well as the support and encouragement they offered one another. Some of these women, including Jane Stafford and Helen Davis, worked together at the Science Service for decades, creating a passionate team which covered some of the biggest news of the twentieth century.

On August 6 of 1945 the United States attacked the Japanese city of Hiroshima, and on August 9 a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. Science journalism had never been more crucial, and Science Service was tasked with explaining this new technology of war to a reeling American public. Five reporters were stationed at the Science Service offices from August 6 to 9, and between them they covered the implications of the atom bomb across chemistry, physics, medicine, biology, psychology and its societal impacts.

“This was the biggest story of [these journalists] lives,” Marcel said.

At the close of August 9 all the Science Service newsroom knew was two bombs had been dropped on civilian cities, but on August 12 the Smyth Report was released, describing the efforts of making the bomb and the journalists had a new challenge. However, unlike the day before, on August 10 only three journalists were present to cover this latest development. All three of them happened to be women. Helen Davis, Jane Stafford and Marjorie Van de Water worked together to get one of the biggest science stories of the century on the wire.

“One of the things that I have come to admire about these women, as I’ve gotten to know them through the years, is their ability to cooperate and collaborate,” Marcel remarked. “The other [is] their concern and empathy for the people outside of the news office.”

The existential realization of the atom bomb certainly required empathetic reporting along with a collaborative effort to keep the American public informed, and these impressive women more than rose to the task.

These triumphs of journalism were joined by more than a fair share of challenges. In covering the field of medicine, Jane Stafford often came up against the sexism. For example, when she was invited to cover a medical seminar only to be told later that she couldn’t attend because it was being held in a men’s-only club. Stafford co-founded the National Association of Science Writers to help give journalists a platform, but she found even that didn’t grant her access when an event was organized to honor the Association at a venue that Stafford was once again barred from entering.

The eight women profiled in Writing for Their Lives fought for their spots in the world of journalism, and in doing so helped build and define the field of science journalism. Throughout Marcel’s book these women shimmer off the pages, coming to life as professionals and individuals passionate about science and the importance of making it accessible for the public.

Writing for Their Lives can be purchased through MIT Press.