‘Jupiter on steroids’: Science News writer talks about discovering a planet

What makes Science News must-read science writing? The deep expertise of its journalists, for one thing. Many are former Ph.D. scientists. And some even publish breakthrough research — like Science News astronomy writer Chris Crockett’s recent paper on discovering one of the youngest Jupiter-mass exoplanets ever found near a newly formed star.

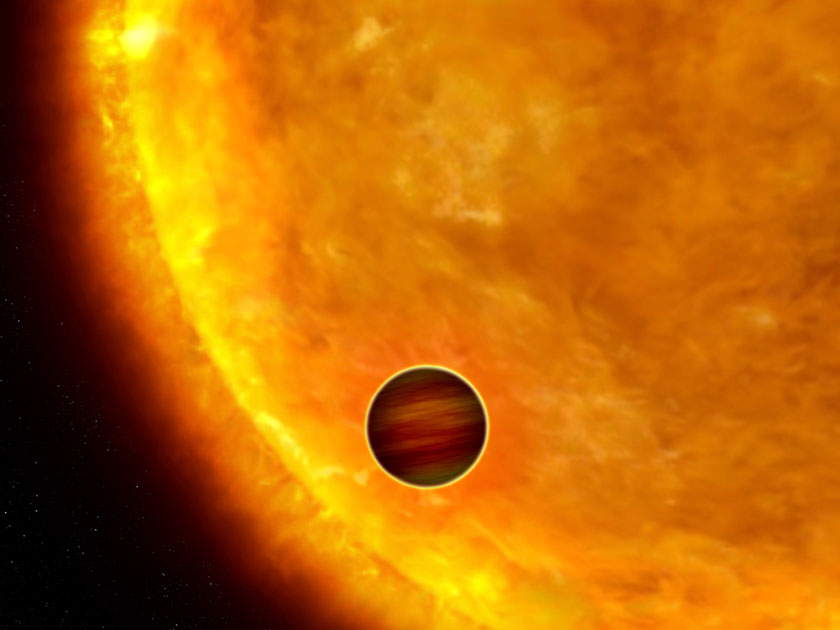

The planet he helped find — CI Tau b — is amazing: A hot gassy ball 11 times the mass of Jupiter, it takes only nine days to orbit its 2-million- year-old star, which is about 450 million light years from Earth, in the constellation Taurus.

Just as amazing, says Chris: CI Tau b is an important missing piece in science’s journey to fully understand how planets form. Learn why below — and also why it took nearly a decade for Chris and his colleagues to confirm that CI Tau b was, in fact, actually a planet.

Q: Your paper came out a few months ago — but you started observing CI Tau b as a graduate student in 2008. Why did it take so long to confirm that it was a planet and not something else?

Chris Crockett: Part of it is that stars are a lot like young people: They’re temperamental and they misbehave. Young stars especially have all sorts of things going on — enormous sun spots, flares, jets, materials orbiting around them. And many of these things, particularly sunspots, can mimic the signals of planets.

Stars are a lot like young people: They’re temperamental and they misbehave.

So people generally avoid looking for planets around these things because it’s just very challenging. When I was a grad student, one of the things I did my thesis on was: Hhow can we distinguish actual planets from things the stars are doing to trick us?

And part of the delay is just the nature of how getting time on telescopes works — sometimes you can only get a night at a time or a week at a time. It takes a lot of time to get enough data.

Q: One of the planet-hunting techniques you used is called “radial velocity monitoring.” You were telling us earlier it’s like tracking a speeding car.

Chris Crockett: Right. You can’t see the planet itself — what you can see is how the planet gravitationally tugs on a star that’s orbiting. As the planet orbits, it’s pulling on the star, the star is wobbling in space, and radial velocity monitoring means that you’re analyzing the light coming from the star and using that to measure the speed that the star is moving, either away from or towards the Earth.

It’s similar to a Doppler shift, and exactly how police catch speeding cars: they bounce radar off a car, and the frequency the radar comes back at is changed, depending on the speed of the car. Instead of bouncing radar off the star, we’re using light that’s already coming from the star.

By looking at how far it wobbles and how fast it wobbles as it moves toward and away from you, you can figure out the mass of the thing that’s tugging on it.

Science: Your passion — our mission. Join the Society today.

Q: CI Tau b seems remarkable: not only is it enormous, but it completes its orbit of CI Tau (and thus its year) in only nine days. But why is it a remarkable astronomical discovery?

Chris Crockett: We’ve been studying exoplanets for 20-25 years, and everything we know about how giant planets form says they shouldn’t snuggle this close to their stars so quickly. Giant planets should form far away, where there’s a lot more material they can form from.

So do these planets form farther out and work their way closer into the star as they’re growing, with their orbits changing along the way? Possibly. We have no observations that show how quickly that happens. But finding CI Tau b tells us one of these giant planets can get placed close to really young stars very quickly — in only a couple million years, which is an eye blink to a planet or star.

It’s almost certainly just a big ball of gas — Jupiter on steroids.

What we really need is to find a whole bunch of these around a whole bunch of different types of stars that have different types of environments around them. A, and then we need to look for commonalities and trends — such as in the disks of materials these planets tend to orbit in. CI Tau b is a great starting point.

Q: What’s CI Tau b’s fate? We’ve read it could eventually fall into the star — or even get ejected into deep space!

Chris Crockett: I would say anything goes at this point. We know these planets are close to stars — but we don’t know why they stop getting closer. Naively, you’d think they’d just keep moving and eventually fall in.

One of the ideas is that, as the planet falls toward the star, the star gets brighter and hotter and eventually just blows away the disk of material that orbits the planet. And since the reason the planet is falling into the star is because of the drag force of the disk, once that disk is gone, the planet stops falling and settles into orbit.

Finding CI Tau b tells us one of these giant planets can get placed close to really young stars very quickly — only a couple million years, which is an eye blink to a planet or star.

The planet could also be ejected from orbit. That would depend on whether there are other planets orbiting the star. If there’s another planet orbiting closer in or farther out, and both of them get into the right gravitational dance, one or the other could get thrown out.

Q: What else do we know about CI Tau b?

Chris Crockett: It’s almost certainly just a big ball of gas — Jupiter on steroids, probably. Also, since the planet is so close to its star, a lot of heat is almost certainly getting dumped into its atmosphere. Is that driving a lot of storms that would put Jupiter’s storms to shame? That’s all speculation.