Intel STS alumna challenges underrepresentation in STEM

Alexa Dantzler, winner of the Intel Science Talent Search 2013 Glenn T. Seaborg award, started an initiative to recruit young minority women into university-level research labs. She is challenging the low-diversity statistics of STEM jobs through Students Obtaining Atlanta Research (SOAR). She believes SOAR will provide a head start for these underrepresented minorities and women by matching them with mentors.

Can you talk about the dearth of representation in research labs and STEM in general? How do you feel representation could improve in STEM fields?

The current situation of minority women involved in STEM is a distressing testament of the untapped potential of young minority women interested in pursuing STEM-related jobs. Women make up 47 percent of the U.S. workforce, according to the Department of Labor. And fewer women are represented in science, technology, and engineering occupations. Racial disparities within the percentage of women in STEM continue to exist. Minority women, mainly African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics, make up less than 1 in 10 women in science and engineering jobs, according to the National Science Foundation.

As a mixed Korean, Slovak, and African American woman, it did not take me long to realize the reality of these statistics in my research experiences. When I was a 2013 Intel STS finalist, I realized I was the only student from a minority background. I wondered why more minority students from African American and Hispanic backgrounds were not represented in our Intel cohort. The Office of Science and Technology Policy, collaborating with the White House Council on Women and Girls, states that the way to combat underrepresentation is to expose minority women to formal and informal science environments, encourage mentoring, and support efforts to retain women in STEM positions. I founded Students Obtaining Atlanta Research (SOAR), which seeks to match high-achieving minority women students from the Atlanta Public School system with prominent research-scientists on the brink of cutting-edge research at Emory University. SOAR is based on the significant student-mentor relationship. I meet with my mentees weekly to discuss the progression of their college plans, receive updates on their SAT/ACT scores, request recommendation letters, and apply to scholarships. I am convinced that this initiative of methodically assessing which students harbor a keen interest in the sciences and helping them conduct university-level research not only increases their participation in STEM but also inspires them to choose a STEM-related job in the future.

Why is it more difficult for women to pursue careers in science?

Inadequate academic preparation in foundational science courses; a lack of emphasis on active engagement in STEM projects, internships, and science fair opportunities; and a lack of the allocation of funds within the school system to build comprehensive, robust, and advanced STEM curriculums collectively leads to fewer minority women tangibly seeing the opportunities in science. In some under-resourced schools where there is no emphasis on the significance of science fair competitions and teachers do not make a strong enough effort to conduct a science fair, students are left unaware about opportunities at regional and national science competitions. Under-resourced schools and curriculums are no excuse to preclude underrepresented students from becoming active in the STEM community.

Why did you start SOAR? Describe your involvement in Atlanta middle and high schools.

I started SOAR because I believe in the power of the mentor-student relationship. If my mentor, Dr. Paul Roepe from Georgetown University, whom I reached out to in high school, had never agreed to help me, I would never have developed an independent research project that would lead to a contribution in the field of environmental toxicology, publication, and selection as a 2013 Intel STS finalist. Starting a career in STEM takes a mentor who will take a chance on the student. The mentor must be willing to share his/her skills, talents, and time with eager students who are ready and prepared to be exposed to new concepts and collaborations within STEM.

I also give motivational STEM talks at inner-city Atlanta middle and high schools. I discuss my high school research and selection as a 2013 Intel STS finalist. I tell students about upcoming national science competitions and available scholarships. I explain how to methodically design an independent research project and write emails to university professors asking for advice or a position in their laboratories. I encourage the middle school students to develop their science fair projects further and enter competitions such as Broadcom MASTERS. I offer the opportunity to match them with potential investigators at Emory University labs and record the students who are interested in conducting university-level research. We draft emails and polish their resumes to distribute to potential mentors. I want my mentees and other students to know that they are never too young to make a discovery.

What has the response been to this initiative? What are your mentees focusing on?

The response has been such a positive one. When my mentees asked to research at Emory, the professors responded within the next 48 hours and agreed to mentor these two young women. My two current mentees were among the first group of students at my STEM talks. Bernabe Becerra, whose family originally emigrated from Mexico 20 years ago, now works as a research assistant in Dr. Meleah Hickman’s lab. Becerra works with Hickman to investigate the genome plasticity and acquisition of antifungal drug resistance in the yeast Candida albicans, which normally harbors in the gastrointestinal track of healthy individuals but can cause serious complications and infection in immunocompromised individuals. Nzinga Hendricks works in Dr. Pin Jeng’s lab. Nzinga is using the lab’s equipment for an independent research project investigating the effect of mutagens on certain checkpoints within breast cancer division and tumorigenesis. Ms. Jacqueline Keeler, the mentees’ International Baccalaureate teacher, said: “Nzinga and Bernabe have really taken the opportunities presented and started on the path they will follow into college and beyond. Through programs like SOAR, students have been able to bridge the gap and quell the fear of college-level academics. They see opportunities instead of barriers.”

Tell us about your research at Emory University.

I am currently a junior (2017 expected graduation) and a Biology and African Studies double major. During my freshman and sophomore years, I worked in Dr. John Petros’ lab in the Department of Urology at the Emory School of Medicine, investigating the role of mitochondrial mutations within the context of the phenomenon known as the Reverse Warburg effect in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer growth. In short, the Reverse Warburg effect states that instead of epithelial cancer cells fueling themselves via glycolysis, the surrounding fibroblasts that are engaging in aerobic glycolysis supplement the main epithelial cancer cell. Little is known about the effect that certain individual mitochondrial mutations have on this process. I have taken a temporary break from research, but I hope to return next year to focus my senior honors thesis on this exciting topic.

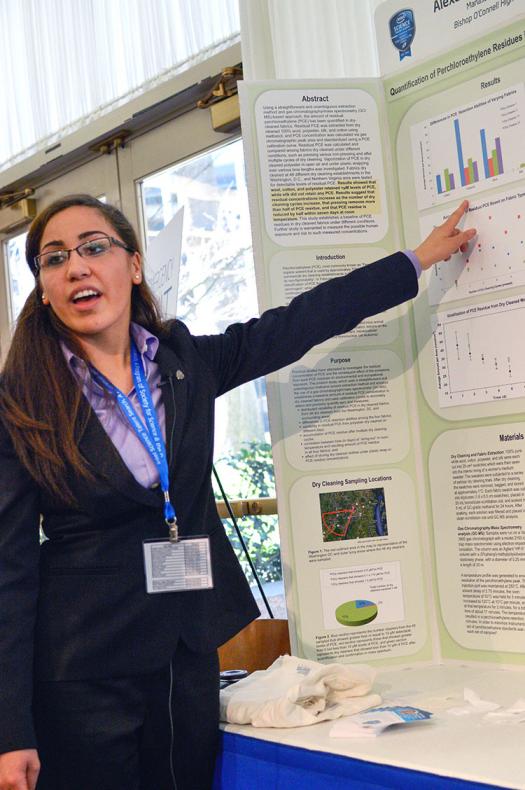

What was your most memorable experience at Intel STS 2013? Can you provide a short description of your research project?

My most memorable experience of Intel STS was by far meeting President Barack Obama, shaking his hand, and having a five-second conversation. My research project provided evidence that the commonly used dry cleaning solvent perchloroethylene, classified as a “potential carcinogen,” could be measured in dry-cleaned fabrics. The solvent residue increased in the fabrics in correlation to an increase in dry cleaning treatments. Different fabrics retain different quantities of these toxic residues, whose fumes have been linked in the dry cleaning workplace to breast, prostate, liver, and kidney cancers among dry cleaning workers.

Did your experience at Intel STS inspire you to push for more representation in STEM?

My experience certainly pushed me to create SOAR. I was no longer content with allowing the statistics to define the scientific community of young, talented student researchers. The national stage of young student scientists should be representative of all the talent, diversity, and potential that exists in this country. I was so happy to have been elected the Glenn Seaborg Winner in 2013, and as I spoke on behalf of the Intel STS finalists on stage that night, I realized that STEM and community activism go hand-in-hand. I was overwhelmed by the support from the crowd. I knew that this type of support is the fuel behind any research project and through SOAR I have created an interconnected web of that support which will provide fuel for my mentees and their STEM goals.

What is your advice to young people interested in science and math?

You have to go outside of your comfort zone. You cannot be afraid to reach out to experts or university professors for advice. These experts want to share their expertise with younger, inquisitive students and cultivate their curiosity. Ask your teachers about science fair opportunities. If there isn’t a formal science fair program at your school, ask your principal to create one.