How to model climate change

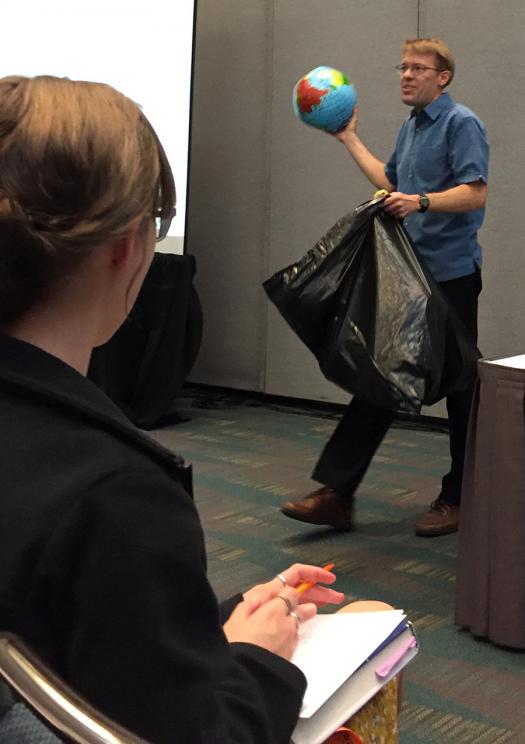

Dozens of inflatable globes were thrown into the audience. Intel ISEF finalists, judges, and fair directors spun their globes, spotting the Gulf Stream, Kuroshio Current, and other important spots.

Mark Petersen, a researcher at Los Alamos National Laboratory, explained different ways of modeling the effects of climate change during his Climate Change, Modeling, and Supercomputers symposia session at Intel ISEF 2017. He used the inflatable globes to show important areas that scientists study, and how different types of modeling work together to model the entire Earth.

Climate change simulations measure high or low fossil fuel scenarios, ocean acidification, rising sea levels, and more. Scientists measure things like how fast ice sheets will melt and ocean modeling.

These climate change models involve physics, chemistry, biology, math, and more. Many fields work together to understand everything that goes into the Earth, and its possible changes. Everything goes back to the roots of physics, to widen it out into examining climate change.

Computing tools can help scientists and the world understand what the effects of climate change are and will be. Resources like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change are invaluable. The IPCC releases a massive report every six-seven years.

“We’re scientists — what do we want? More data,” Mark said.

Scientists are using and finding data from many, many years ago with ice cores. “The wonderful thing about this is that there’s a record of Earth’s climate in Greenland and Antarctica for us to drill,” he said.

With bubbles in the ice, scientists can count layers and “actually go back almost a million years and measure the carbon dioxide concentration,” Mark said. This is a history of carbon dioxide in the air over the last million years. Currently, the amount of carbon dioxide in the air averages about 404 ppm, which is “well outside anything in the range of the world’s history,” he said. Homo sapiens have been around for two ice ages, and regularly the level was at 180-220 ppm.

In the last several million years, the Earth’s climate was mostly very cold. Ice ages lasted about a hundred thousand years. And for ten thousand years in between them, there was an inter-glacial period where the Earth warmed up. “It’s really because of glacial ice ages that we had such a stable climate to develop agriculture,” he said.

Humans [and our technology] emit[s] carbon dioxide, the concentration in the air is increasing, and half of it goes into the ocean. The pH level of the ocean decreases because it’s taking in carbon.

Carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are tricky. “Like a roach motel, greenhouse gases can come in, but they can’t come out,” Mark said.

Other questions involve the Gulf Stream’s course and strength. If it weakens, will that make Europe colder?

And scientists also research coupled climate models and effects, because the oceans don’t exist by themselves — it’s just one part of the climate system, Mark explained. Coupled models include the ocean, atmosphere, land surface, land ice, and sea ice. These coupled models must talk to each other for scientists to understand how the Earth may truly be affected by climate change.