Lemelson Foundation, Young & Amazing

Harvesting wild algae to make paper

Annually for three years, The Lemelson Foundation will give $100 awards to outstanding inventors in up to 270 Society Affiliate Fairs with middle school participants around the country. The prize was specially created to reward young people whose projects exemplify the ideals of inventive thinking by identifying a challenge in their community and creating solutions that will improve lives.

Invasive algae are often found in bodies of water such as lakes and ponds, but can it be used as paper? Seventh-graders, Wyatt Vick and Charley Clyne, from Zane Trace Middle School in Chillicothe, Ohio, set out to answer that question with their project, “Algae Paper,” eventually earning them the Lemelson Early Inventor Prize.

The idea to investigate algae as a possible paper source came to Wyatt and Charley one day while fishing. “The water level had gone down and we saw dry algae around the edges of the pond—it resembled paper. I could even fold an origami crane out of it,” said Wyatt. “There have been a few studies about the use of algae as paper, but most of what we found was about using red algae specifically for paper products, but they performed poorly in tests.”

Motivated by their concern for the environment, as well as wildlife and human health, the young investigators researched ways to diminish the negative effects associated with papermaking. “Many trees are cut down, resulting in erosion and loss of animal habitat.” Through their research, the boys learned that harvesting algae during algal blooms (the rapid growth of algae in aquatic systems), could help the environment while also creating a valuable product.

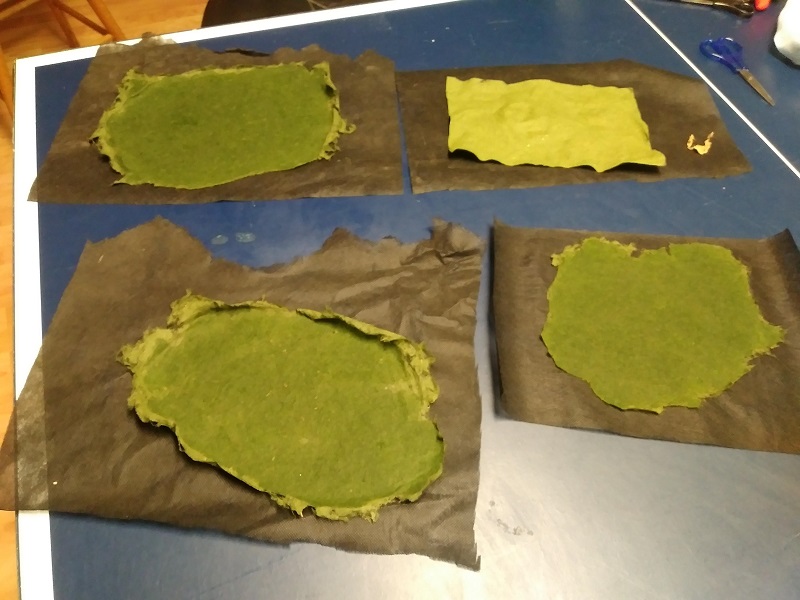

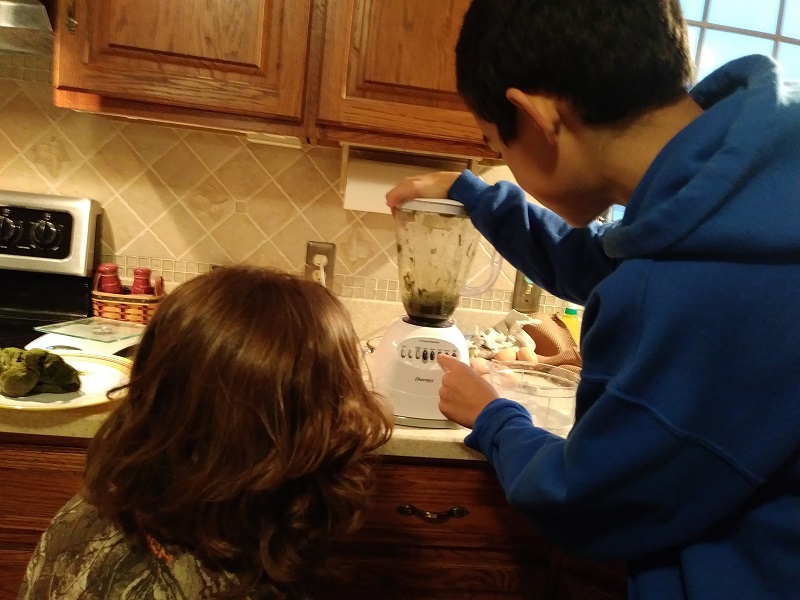

In order to transform the collected algae into paper, Wyatt and Charley first removed extraneous debris such as leaves, twigs, snails and beetles. Next, they boiled the algae in water for ten minutes before blending the mixture until smooth. Then, they spread the mixture over a screen to get rid of excess water, flattened the remains with a rolling pin and finally left it out to dry.

“The best part was taking the algae paper off of the screen when it was ready. That was very satisfying,” Wyatt reflected. “The hardest part was spreading the algae evenly. We tried many techniques until we found one that worked. We also studied the actual paper-making process to make our paper in a similar way.”

Wyatt and Charley made two types of algae paper—one with and without cornstarch. They compared their algae-based papers to commonly used paper products—printer paper and paper towels.

“We performed three different tests on four types of paper. First was a strength test in which a small strip of each paper type was suspended over the edge of a table. We added weight to one end of the strip until it tore. Printer paper held the most weight followed by algae paper. Paper towels and our algae-cornstarch paper performed poorly. Our second test was a burst test, which had the same setup with the addition of a drop of water in the middle of each paper strip. Our algae paper without cornstarch was the strongest by far. The third test was the absorption test. We submerged a strip of each paper into water for ten seconds and recorded the amount of water absorbed. Our two algae-based papers absorbed much more water than the other papers.”

After winning the Lemelson Early Inventor Prize, Wyatt and Charley now see themselves as inventors, but have always enjoyed building things. “My partner and I have done science fair for three years,” Wyatt explained. “I prefer working in a team to inventing alone because you can be more creative with two people,” Wyatt noted.

Wyatt and Charley have plans to continue improving their algae paper. “We recently found a substance in cattails (wetland plants) that we will try to add as a bonding agent because cornstarch did not work well. We might also test different species of algae and test to see if it leads to stronger paper. We are hoping that our paper could be used as an art material or a cheap, biodegradable landscaping fabric.” With recent global attention tuned in to sustainability initiatives from climate change to deforestation, Wyatt and Charley hope their science will be able to contribute to these efforts.