Frugal science: Building an army of scientists around the world

Growing up in India, Manu Prakash couldn’t afford a microscope. He challenged his brother and himself that he would build one out of cardboard and duct tape. So he stole the fat lenses from his brother’s glasses and created his own.

“My brother was not happy,” Manu said, “but that was the moment that changed my trajectory into science.”

Now, Manu is the co-inventor of a foldable paper microscope that costs less than $1 to make. He’s donated the Foldscope to people around the world — 50,000 so far to hundreds of countries, with plans to donate a million. These paper scientific tools don’t require electricity and can withstand the rigors of the field.

Manu discussed his STEM journey and offered advice to the Intel ISEF 2017 finalists. He believes and practices frugal science, the idea that science is for everyone, not just for the people who have access to it or the money to get resources.

“We need a lot more people thinking about these problems,” he said. “It’s possible to make these instruments completely human-powered.”

Manu’s approach to frugal science is to give himself a lot of constraints when trying to invent solutions or tools that would survive in the field without electricity or in rural clinics. For instance, the Foldscope is built out of origami, weighs less than 10 grams, and offers 700 nanometer resolution.

Once he donated Foldscopes, one community in Madagascar created paintings of species they found in their backyards.

We need a lot more people thinking about these problems. It’s possible to make these instruments completely human-powered.

He also created a paper centrifuge, based on a whirligig toy. You can prick your finger, get a drop of blood, and do sample prep with the whirligig that is completely human-powered. In a rural clinic in Madagascar, doctors were using a large centrifuge as a doorstop because they hadn’t had electricity in the area for five years and couldn’t power the tool. The whirligig is able to spin as fast as 1 million rpm, enough to separate blood plasma and parasites.

“You’ve got to share what you do with others,” Manu said. “The real power is within the community, not in the tool.”

Manu encouraged the finalists to become mentors for others. “I can make as many microscopes as are needed, but I cannot make mentors,” he said.

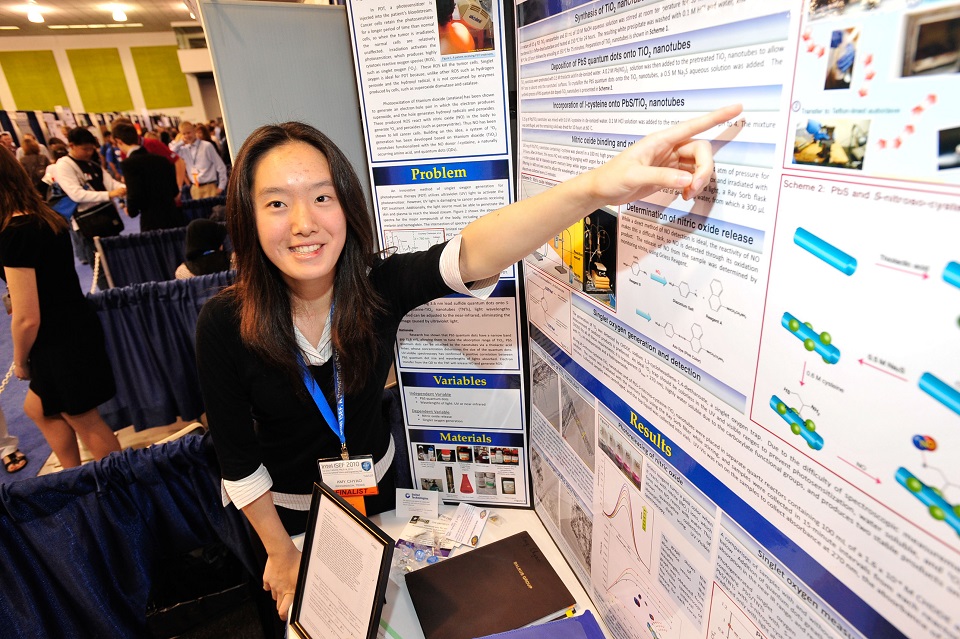

Earlier in the day, Manu snuck into the poster exhibition room, where the nearly 2,000 finalists display their projects, and was “absolutely inspired by the creativity I see in that room and the grace and humility you bring to science.”

You’ve got to share what you do with others.

Manu admitted that he’s been feeling depressed with the current state of science denial and other challenges. “I’ve been depressed, but not anymore,” he said. “I see in you a future.”

The world is living through very tough times, Manu explained. “Climate change, biodiversity loss, science denial. It’s daunting. But solutions are sprinkled everywhere,” he said. “We have to build an army of scientists around the world.”

We have to build an army of scientists around the world.

Once you leave this room, Manu said, engage others in science. “Share your passion for science to the people who can’t afford it,” he said. “Science is not a sprint, it’s a marathon. And I’m so honored to be here at the starting line with all of you in this marathon.”