Educator creates Advanced STEM Research Laboratory for students

My motto is to not so much teach science and engineering, but create scientists and engineers.

This motto propelled Jeffrey Wehr, a science educator from rural Washington, to develop the Advanced STEM Research (ASR) Laboratory. ASR is a yearlong independent study within any scientific/engineering discipline at Odessa High School.

ASR extends past teacher-driven inquiry- students create real questions regarding their worldly observations, formulate a hypothesis or engineering goal, develop a method of experimentation, analyze the data set, and discuss the details of their results in a concise, scientific manner.

Read how Wehr was able to launch and sustain his successful research program, responsible for a number of incredible Intel ISEF finalists.

Can you describe the logistics of your research program?

Having conducted science research prior to teaching, I decided to incorporate my research skills into creating student-driven, research-based STEM activities such as a 2nd Quarter Research project. Most of the laboratories in my regular courses are student-driven and research-based, however I wanted the students to create their own independent STEM research from scratch.

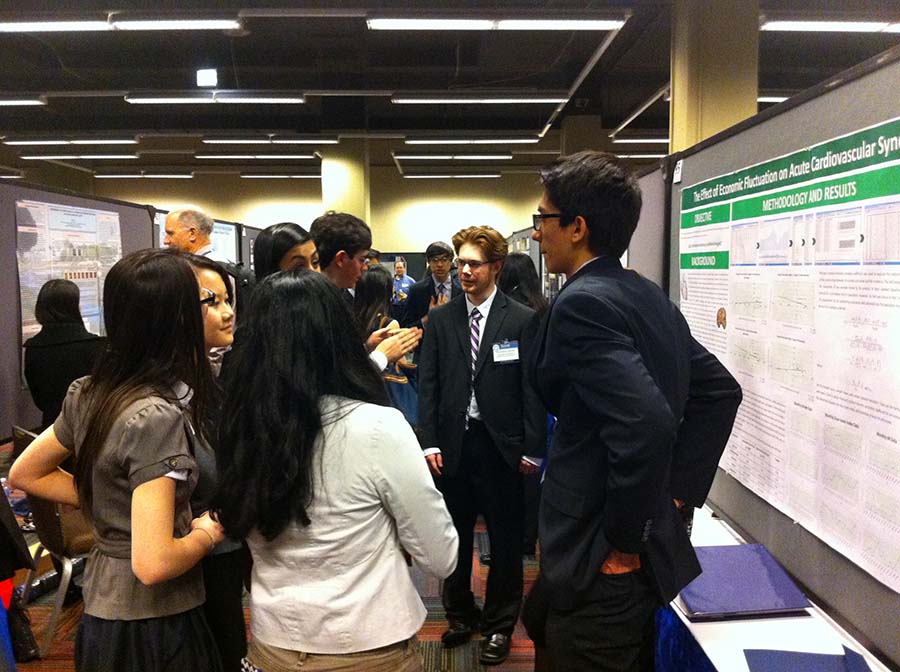

A few years later, I found many students wanting to further their research so I developed and implemented an Advanced STEM Research Laboratory. Students gather and statistically/mathematically analyze their data, while keeping a research journal of their work. Using their research journal, students create a research paper in scientific journal format and a presentation to convey their findings to the scientific community for peer review.

What are the aspects of your program that you think work best?

Treatment, collaboration, and time. I treat my students like they are the expert in their field, and by the end of the year, I expect them to surpass my own knowledge. I interact with my students as peers instead of building the teacher / student wall. I ask what they think, how they know, or what evidence supports their questioning? Then, they go to work on background research and building relationships with other professionals in their field. By the end of the year, I have learned so much from their research, it’s fascinating!

Collaboration is another aspect that is a must in science; my students collaborate with one another, with me, other professionals, their parents, other students, other districts, and community members. By bouncing ideas and thoughts off of everyone, it strengthens their research as well as our ASR Laboratory.

Since time seems to be against us, I developed dedicated class time for the Advanced STEM Research Laboratory. That dedicated hour each day allows the students to thoroughly explore their research.

What has been the most difficult part of running a high school research program?

One of the initial difficulties of running a research program was changing public opinion of what research means; most of the adults and students I chatted with thought- and I still run across this today- that a research program means “science fair.” The public has this antiquated model of students creating baking soda and vinegar volcanoes hoping to win a blue ribbon somewhere down the line; they look at research as a competition, and that turns some people off. I make sure to educate my colleagues, teachers, students, and the public that no scientist ever begins research with the expectation of earning a Nobel Prize.

We research to find answers to questions. Whether the scientific track the student follows is on or off does not matter either! Some of the best educational moments originate from error or inaccuracies. But once the students feel their research is complete, it is their duty as scientists to undergo peer review–to see if their colleagues might agree or disagree with their findings. I try to educate the public that this is what programs such as Intel ISEF, Broadcom MASTERS, or Intel STS are really all about: collaborating with their peers as students, scientists, and engineers.

I also invite the public to our research laboratory and have students reveal how far we have come since baking soda and vinegar volcanoes! Overcoming public opinion has allowed my students to strive for careers in science and engineering, instead of seeing it only as a class they take in school.

How do you make sure your students have the resources they need to succeed?

My students reach out to the global community as resources to help assist them during their experimentation process. Due to our rural nature, the students utilize online crowdsourcing for research support, connecting professionals across the planet with the students. Often the students are invited to research facilities for collaboration, laboratory time, supplies, or presenting their research.

It is not easy though, and writing skills are a definite advantage. Being able to draft a professional contact letter or email describing the nature of their research is critical. But, we have found most universities and research facilities are very open to provide a variety of resources for passionate students. And, over the years, student success has led to grants and donations outfitting our own laboratory with a variety of excellent technology, supplies, and resources.

What is the biggest challenge high school researchers face? How do you help them overcome this challenge?

Honestly, I have met very few students that are not excited for science once they have the freedom to explore their own questions. When talking with students from other districts, they wish they had a research program or at least could conduct some sort of student-driven, research-based STEM activity. Therefore, one large challenge I see is getting more science educators on-board to facilitate student research.

I remind my science education colleagues that we are scientists first and need to retain this privilege as we continue our scientific careers. Educators should try to transform their classrooms into thriving research laboratories! I want my students to see me as a lead scientist in our lab guiding them toward a better understanding of the universe.

A student-driven, research-based classroom or course begins with educators breaking free from teaching science only from a textbook or lecture, and doing science that is applicable to the students. When the students see you trust them to choose their own pathway, real relationships are formed–as well as student integrity and independence. Once that challenge is overcome, students sail to new scientific heights and understanding.

Do you have any other tips you’d like to share? Let us know!

A research program does not happen overnight, and like science, it will stumble along the way. If the students have not experienced academic freedom, educators have to guide them through this process. A lot of high-achieving students do not always make the best candidates for research, since there is not an answer book they can go to when they are struggling.

I like this about research; it is for all students, no matter where they are at on the academic spectrum. All students can have success with research; it just takes time for both student and educator to get there.

Are you a teacher conducting a research program? We’d love to hear more about your experiences. Please contact us!