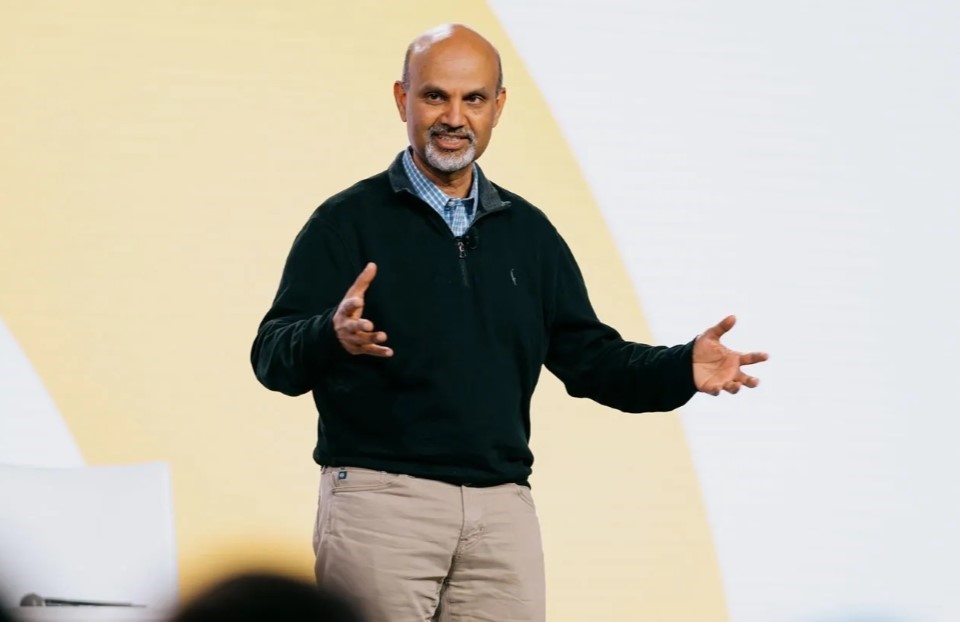

Conversations with Maya: Mohamad Ali

Maya Ajmera, President & CEO of the Society for Science and Executive Publisher of Science News, chatted with Mohamad Ali, Senior Vice President for IBM Consulting, IBM’s global professional consulting services unit. The global organization spans 150 countries and solves complex problems using technology-based assets and AI. Ali is a 1988 alumnus of the Science Talent Search (STS), a program of Society for Science.

How did participating in STS impact your life? Do you have any favorite memories from that competition?

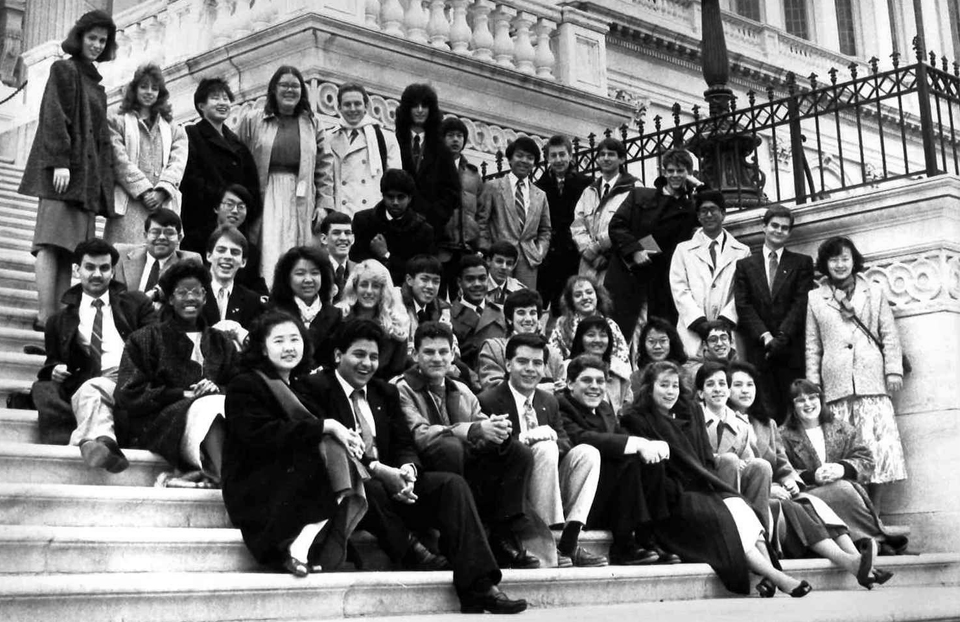

I have several memories that I fondly remember. When I visited Washington, D.C., to compete in STS, I visited the U.S. Capitol, a place I had never visited before. It was such an amazing experience. I also met Nobel Prize winners during the competition. I’m a kid from Queens. I’m not supposed to meet Nobel Prize winners. The whole experience was just incredibly inspirational.

Beyond the event itself, the two years that led up to it were impactful, from researching my project to learning how to write a high-caliber paper that other scientists could read. I would say that, in some ways, STS set my life on its trajectory.

What led you to pursue science?

I’m from Guyana, a small country near Venezuela that very few people have ever heard of. I came to the United States when I was 11, and we didn’t have much. Everything was new; everything was different. In some ways, the fact that I came from such a humble background and was able to compete in STS is one of the wonderful things about STS. It finds students wherever they are.

We moved to Queens when we came to the United States, and I went to junior high school and high school. I struggled with my language-based classes, but numbers were the same in any language. So, math and physics became my friends. One of my teachers in junior high school suggested that I apply to Stuyvesant High School, one of New York City’s specialized high schools. While at Stuyvesant, a woodshop teacher encouraged me to get involved in scientific research. I started doing solar-focused projects and eventually, he recommended that I do a project that the STS program could be interested in.

I decided to do a fusion project, but I wasn’t clear on how one could do a fusion project while in high school. My teacher recommended that I call some people at Columbia University to see if anyone was working on the subject, and I ended up connecting with Michael E. Mauel, who still teaches at Columbia today. He said I could work with him, and we started building a machine to simulate how particles would behave in a magnetic field. Then we ran experiments that were the basis for a paper.

In some ways, it was a series of accidents, from meeting that teacher in junior high school to meeting my woodshop teacher to having the good luck of Mauel inviting me to his lab. All of those accidental meetings, combined with the fact that people were willing to help me, had a huge impact on my life’s path.

Over the course of your career, you’ve worked on the leading edge of both technology and industry. Can you tell us a little bit about your professional journey?

After STS, I went on to Stanford University, and then I worked for a neural network start-up. Then, I joined IBM for 14 years. I worked elsewhere in the industry, including HP, Carbonite and IDG, for the next 14 years, and now I’m back at IBM where I’m working on neural networks and AI. The company’s interest in generative AI technology and new quantum computing technologies is such an exciting opportunity. Personally, I think IBM is leading the world in quantum computing. I’m very excited to see what kinds of problems quantum computing can solve for humanity.

What excites you most about the changing AI landscape?

I am most excited about the problems that these new technologies are going to be able to solve. Of course, that’s both a good thing and a bad thing. Tremendous technologies in the wrong hands or not managed responsibly could be used for purposes that are not for the betterment of society.

That is part of why I came back to IBM. The technologies that are coming to the world now are extraordinarily powerful, and I want to work on them for a company that I believe prioritizes ethics. Leveraging these extraordinarily powerful AI and quantum technologies in a responsible way, where we know how the AI models are trained, we know where the data comes from and we know what kind of biases are present, we can put bounds on the decisions that can be made. We need these kinds of powerful technologies to solve problems like climate change.

You’ve been an outspoken advocate for increasing diversity in tech. Why do you think this is important?

In some ways it’s personal. I came from an underserved community, and because of the teachers that I encountered and because of institutions like Stuyvesant and STS, I got an “at bat.” I got an opportunity to contribute. The world would be a much better place if everyone was able to bring their best and contribute. There is a very good chance that the cure for cancer lies in the brain of a child in one of our poorest communities. We need to give that kid a chance to bring that cure to society. After having lived it, I see the value of giving opportunities to everyone who is willing to take them.

What advice do you have for young people just starting out in higher education or their careers?

I can only speak from my own experience and what worked for me, but I would say this: Study hard and enjoy it. You don’t know what you don’t know. That’s a complicated sentence, but for me I always thought I knew everything. But I didn’t. Learning helps you discover those things. Some of the things that you are going to discover will change your life dramatically — hopefully for the better. Learn as much as you can and keep learning all your life.

Who inspired you as a young person, and who inspires you today?

I was inspired by the great scientists: Einstein, Ada Lovelace and Marie Curie. They all wanted to solve problems and make the world a better place. Today it’s very similar. I am inspired by all the people who are working to solve hard problems with science and then bring those solutions to society in a responsible way.

IBM has committed to training 2 million people, primarily from underserved communities, in AI over the next three years. You can be concerned about AI, or you can embrace it, put it in your tool set and become even more valuable than you are today. Many companies like ours that are leading scientific innovation are embracing AI in a way that helps society, which I think is inspirational.

There are many challenges facing the world today. What keeps you up at night, and what gives you hope for the future?

There are a lot of challenges: global geopolitical instability and war, for example. We have more war now than we’ve had in a while. And people are migrating because of war and because of climate change.

Once again, my response is informed by my own background of growing up in a poor community. Now that I can afford to give back, I contribute to organizations like Oxfam, where I served on the board of directors for 10 years. Those kinds of organizations give me hope, knowing that there are people out there working hard to make our world a better place.

Sometimes it’s a little scary that humanity waits until it reaches a precipice before it starts acting. But time and time again, we have acted as a human race. I tend to be just an inherently hopeful person, and given the capabilities that I see in the world brought by science and technology, I am hopeful.