How did one rural state triple its student science engagement?

Getting teens in rural states more involved in science can be an enduring challenge. In Maine, with only one interstate highway, many educational communities face isolation and seclusion. Stefany Burrell, STEM Education Specialist at the Maine Mathematics and Science Alliance (MMSA), is addressing these concerns by working to expand STEM education opportunities for students across her state.

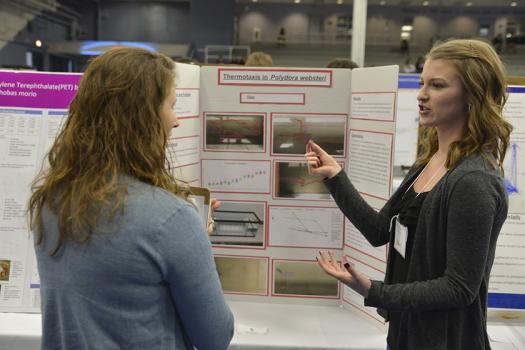

Thanks in part to Stefany’s efforts, an increasing number of students are participating in the Maine State Science Fair (MSSF), sponsored by The Jackson Laboratory and the Reach Center at MMSA. Stefany spoke at Intel ISEF 2018 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, about her experiences, inspiring a new crowd of people who want to grow rural science fairs in their own areas.

Teachers are overworked and underpaid. Schools will pay for a sports coach but don’t seem to value a STEM coach in the same way.

“We find that in rural areas, there might be one science teacher for the whole high school,” she said. Due to this clear limitation in resources and access, Stefany’s organization, MMSA, has made it a point to reach out to more rural schools. “Teachers are overworked and underpaid. Schools will pay for a sports coach but don’t seem to value a STEM coach in the same way.” Thanks to an expansion of STEM opportunities and making some key changes to how they support teachers—science fair participation in the state has nearly tripled.

But how has Maine accomplished this increased participation when schools have limited resources?

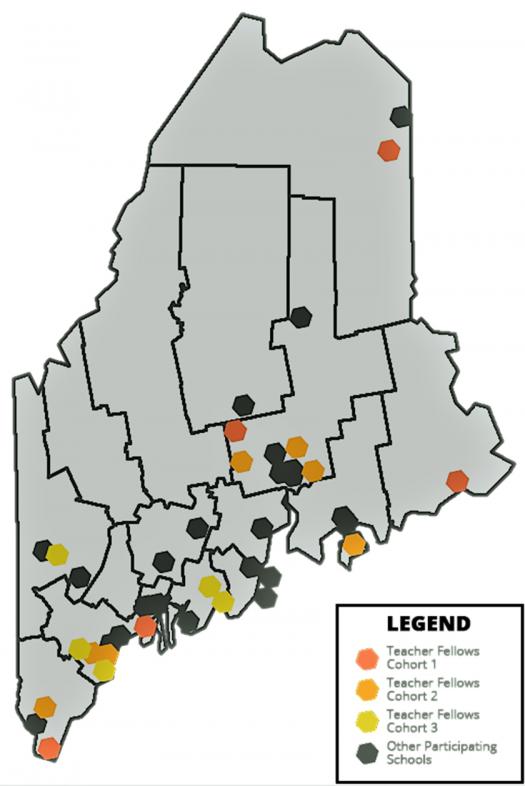

One way has been through a teaching fellows program, sponsored by MMSA. The Jackson Laboratory assists with the training as well. The program offers numerous professional development opportunities, including an annual summer institute. Teachers learn to better support students with independent science and engineering projects. After the summer institute, the teachers have access to direct support from the MSSF staff and a set of resources online.

Time is often a barrier for teachers looking to support students in hands-on research in light of demanding state and national instructional requirements. Stefany therefore encourages teachers to consider science fairs as extended learning opportunities that feed students’ natural curiosity, motivating them to compete in science fairs.

Consider science fairs as extended learning opportunities that feed students’ natural curiosity.

“Some of the things we did came at little to no cost to us – such as asking colleges to give scholarships. Other things did require a budget, such as our Teacher Fellows program, but there are aspects of it that can be implemented at a fairly low cost,” Stefany explained.

For example, the organization invested in Scienteer, an online science fair management platform that helps make filling out science fair forms easy for students and teachers. The system, which is similar to Turbo Tax, also makes things easier for the science fair. “We no longer need to worry about keeping track of a bunch of paperwork, and the teachers who’ve experienced the before and after of using Scienteer really like it. It’s been a small expense that’s made a big difference,” Stefany said.

Some of the bigger Maine schools are getting more students involved in research by offering research methods courses, but for rural schools with a small staff of STEM teachers, starting a research class dedicated to completing science fair projects is unlikely. According to Stefany, however, some schools are including research projects in their traditional science course syllabi. One Maine school offered the incentive of honors distinction to students who participated in the state fair. Similarly, one teaching fellow began a movement to offer a STEM diploma endorsement.

Stefany tells students and parents to keep in touch with her, particularly if the school isn’t doing so. “I like it when students check in, because our goal is to help students build skills and be able to communicate about their project management process,” she said,

I like it when students check in, because our goal is to help students build skills and be able to communicate about their project management process.

Maine’s science fair was originally very small. With increased engagement, the difference has been mammoth. Stefany explains, “With only about 10 schools and 100 projects, we had a lot of room to grow. Our state has approximately 125 high schools and with our Teacher Fellows program we engaged a group of teachers who just needed a bit of support to try it for the first time.” Within the second year of the Fellows program, many schools have institutionalized science fair participation.

One of Stefany’s goals is to help teachers in rural areas build science fair projects around issues they are passionate about. Stefany describes a teacher who works with students to observe great blue herons unique to their region, while another teacher is working with local Atlantic salmon. With these niche passions, teachers are able to connect with students about science in genuine ways and take advantage of the natural surroundings.

Additionally, Stefany uses the STEM network in Maine to develop her efforts. Through word of mouth, and networking, MSSF is seeing more and more students become involved. She said, “If a student is involved with the University’s Stormwater Management program, or doing research through Upward Bound over the summer, science fair can be a value added that could lead to awards, scholarships, or even a trip to ISEF.”