Fireside chat with educator, Devon Riter: Sparking a passion for STEM in Native American students

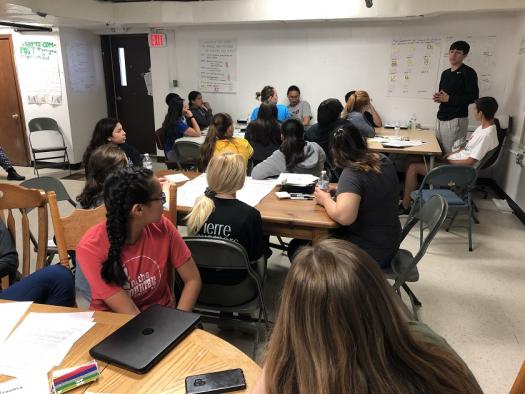

At the 2019 High School Research Teachers Conference, educators from 46 states across the U.S. came together in the nation’s capital to discuss key STEM education topics and effective methods for teaching students science. This year, the conference included a new format—fireside chats—giving attendees an opportunity to converse in an intimate setting. There were 20 fireside chats in total.

Devon Riter, a teacher and Society Advocate, led a chat about best practices for teaching STEM to Native American students. For the past five years, Devon has taught science classes to 7th-12th graders at Lower Brule High School, located on the Lower Brule Sioux Reservation in South Dakota. Devon’s organization, Lower Brule Research, also received a STEM Action Grant last year. Working in a small school system, made up of just 350 students, gives him the freedom to be creative and craft a curriculum that will resonate with his students.

Devon asserts that as a white man teaching Native American students, “I am aware of my privilege. I feel it’s important to understand how to use this power to help address any barriers that may be impeding my students’ path to success.” Devon shared that he bases his educational philosophy on a long history of culturally responsive approaches advocated for by Indigenous educational leaders like Bryan Brayboy.

“I listen to my students, their families and community members to try to understand what is important to my students and incorporate opportunities to explore those passions into the curriculum, hopefully helping students find deeper intrinsic value in science education. I am far from perfect in this regard and struggle every day to try to understand how to make my classroom more culturally responsive,” said Devon.

Devon shared the example of how some of his students are not interested in esoteric biology or chemistry concepts taught in traditional science textbooks, but they may be keen to learn about the environmental implications of pipelines cutting through Native lands, something that would directly impact them.

“Taking a culturally responsive approach to STEM education means students from different backgrounds will have the opportunity to explore these backgrounds within their science classroom. This approach scares many people who fear that differentiating instruction among students will lead to expanding the divisions we see in our country. I take a counter perspective—the differences between groups and individuals provide perspectives that we will need to solve the scientific challenges facing our society,” Devon said.

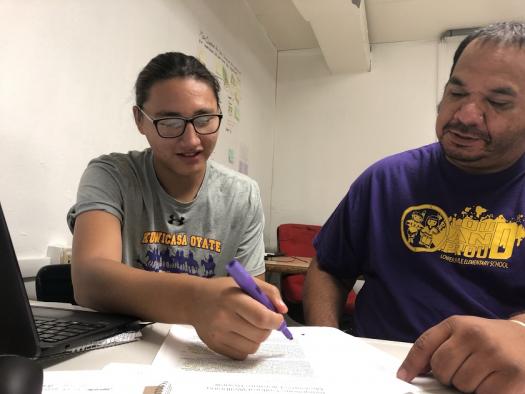

To this end, Devon encourages his students to direct their own research projects and supports their exploration of topics that pull in cultural or social justice issues. For example, this summer Devon worked with a group of students who took a social science approach to examine the role of historical trauma on youth involvement in Lakota culture. The results of their work contained valuable insights not just for Native American communities but for social science and broader society. Devon explained that, “This type of work shows that we need diverse perspectives and a broad range of scientific efforts like those conducted by students to gain a deeper understanding of our world and what we should do to try to make it better.”

Other educators echoed Devon’s views. For instance, Whitney Aragaki from Waiakea High School in Hilo, Hawaii, mentioned her students’ interest in the Mauna Kea protests occurring in their state. These are a series of protests about the placement of a visible-light telescope on a mountain considered sacred. Teachers chatted about how this issue is one that students are passionate about discussing and directly relates to the people of Hawaii and the advancement of science. The teachers suggested this as one of many examples of how science can be framed within a context that is personal and meaningful.

When teaching Native students, Whitney elaborated that it is important to be conscious of the term success. For these students, success can mean pursuing a formal education and career that are off the reservation. She shed light on challenging attitudes tribe members sometimes have when Native members leave the community to pursue an education in STEM fields or otherwise. Particularly for Native students who are interested in pursuing science, that sometimes means leaving the reservation in search of research opportunities in a lab, opportunities unavailable to them on the reservation. However, those who do leave can be perceived as being a “sell out” or “too good” for those they grew up with. “Native students tend to carry a greater sense of alienation, if they are focused on academia,” Whitney explained, but she believes that one can retain their heritage and culture while gaining a formal, higher education.

The fireside chat with Devon was a critical forum to discuss key topics, but the main takeaway was that teaching methods must be adapted to the student body. The teachers who attended Devon’s fireside chat are creating value and helping their students through an open-mindedness and willingness to learn.